150 years ago today Lieutenant William Cushing

executed one of the most daring raids in United States military

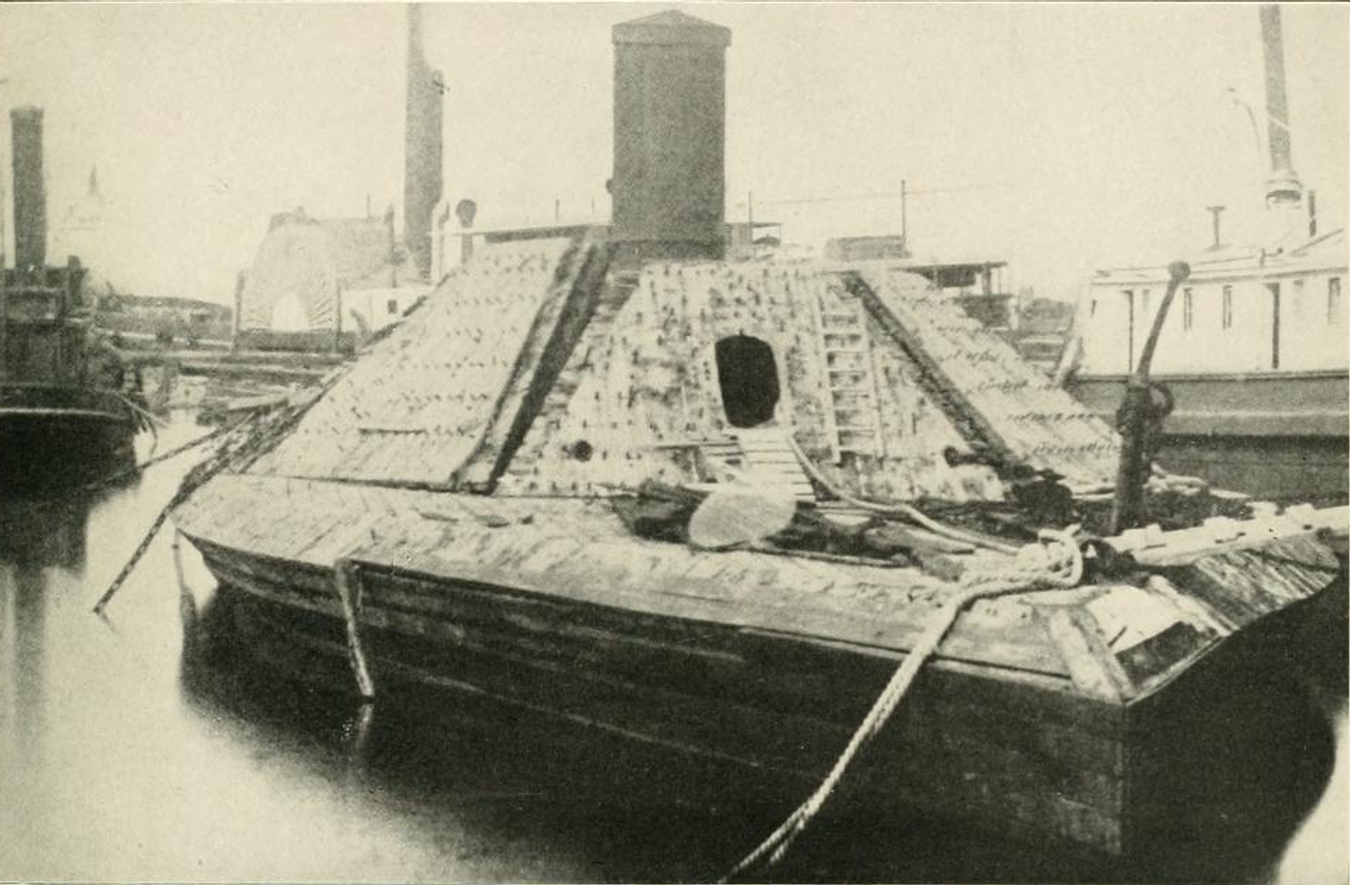

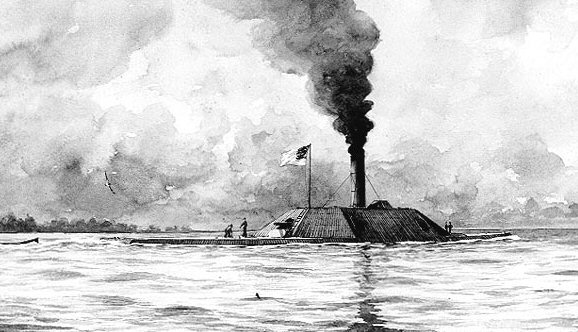

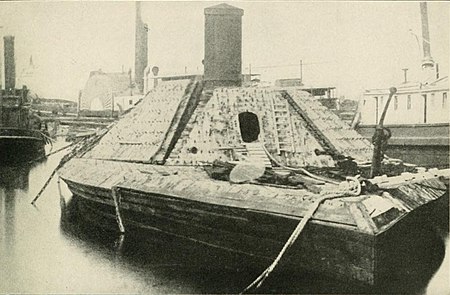

history – the sinking of the CSS Albemarle. Since its defeat

of several Union ships in April, the Albemarle had remained in

control of a sizable portion of the Roanoke River. The Federals

wanted to end that, and Cushing volunteered to lead two small boats

to try to sink her. He wrote this in a magazine article describing

the attack:

I intended that one boat should dash in, while the other stood by to

throw canister and renew the attempt [on the Albemarle] if the

first should fail. It would useful to pick up our men if the

attacking boat were disabled. Admiral Lee believed that the plan was

a good one, and ordered me to Washington to submit it to the

Secretary of the Navy. Mr. Fox, the Assistant Secretary of the Navy,

doubted the merit of the project, but concluded to order me to New

York to “purchase suitable vessels.”

Finding some boats building for picket duty, I selected two, and

proceeded to fit them out. They were open launches, about thirty feet

in length, with small engines, and propelled by a screw. A 12-pounder

howitzer was fitted to the bow of each, and a boom was rigged out,

some fourteen feet in length, swinging by a goose-neck hinge to the

bluff of the bow. A topping lift, carried to a stanchion inboard,

raised or lowered it, and the torpedo was fitted into an iron slide

at the end. This was intended to be detached from the boom by means

of a heel-jigger leading inboard, and to be exploded by another line,

connecting with a pin, which held a grape-shot over a nipple and cap.

The torpedo was the invention of Engineer Lay of the Navy, and was

introduced by Chief Engineer Wood.

Everything being completed, we started to the southward, taking the

boats through the canals to Chesapeake Bay, and losing one in going

down to Norfolk. This was a great misfortune, and I have never

understood how it occurred. … My best boat being thus lost, I

proceeded with one alone to make my way through the Chesapeake and

Albemarle canals into the sounds. …

The Roanoke River is a stream averaging 150 yards in width, and quite

deep. Eight miles from the mouth was the town of Plymouth, where the

ram was moored. Several thousand soldiers occupied the town and

forts, and held both banks of the stream. A mile below the ram was

the wreck of the Southfield, with hurricane deck above water,

and on this a guard was stationed, to give notice of anything

suspicious, and to send up fire-rockets in case of an attack. Thus it

seemed impossible to surprise them, or to attack, with hope of

success.

Impossibilities are for the timid: we determined to overcome all

obstacles. On the night of the 27th of October [1864] we entered the

river, taking in tow a small cutter with a few men, the duty of whom

was to dash aboard the Southfield at the first hail, and

prevent any rocket from being ignited.

Fortune was with our little boat, and we actually passed within

thirty feet of the pickets without discovery and neared the wharf,

where the rebels all lay unconscious. I now thought that it might be

better to board her, and “take her alive,” having in the two

boats twenty men well armed with revolvers, cutlasses, and

hand-grenades. To be sure, there were ten times our number on the

ship and thousands near by; but a surprise is everything, and I

thought if her fasts were cut at the instant of boarding, we might

overcome those on board, take her into the stream, and use her iron

sides to protect us afterward from the forts. Knowing the town, I

concluded to land at the lower wharf, creep around and suddenly dash

aboard from the bank; but just as I was sheering in close to the

wharf, a hail came, sharp and quick from the iron-clad, and in an

instant was repeated. I at once directed the cutter to cast off, and

go down to capture the guard left in our rear, and ordering all steam

went at the dark mountain of iron in front of us. A heavy fire was at

once opened upon us, not only from the ship, but from men stationed

on the shore. This did not disable us, and we neared them rapidly. A

large fire now blazed upon the bank, and by its light I discovered

the unfortunate fact that there was a circle of logs around the

Albemarle, boomed well out from her side, with the very

intention of preventing the action of torpedoes. To examine them more

closely, I ran alongside until amidships, received the enemy’s

fire, and sheered off for the purpose of turning, a hundred yards

away, and going at the booms squarely, at right angles, trusting to

their having been long enough in the water to have become slimy—in

which case my boat, under full headway, would bump up against them

and slip over into the pen with the ram. This was my only chance of

success, and once over the obstruction my boat would never get out

again; but I was there to accomplish an important object, and to die,

if needs be, was but a duty. As I turned, the whole back of my coat

was torn out by buckshot, and the sole of my shoe was carried away.

The fire was very severe.

In a lull of the firing, the captain hailed us, again demanding what

boat it was. All my men gave some comical answers, and mine was a

dose of canister, which I sent among them from the howitzer, buzzing

and singing against the iron ribs and into the mass of men standing

by the fire upon the shore. In another instant we had struck the logs

and were over, with headway nearly gone, slowly forging up under the

enemy’s quarter-port. Ten feet from us the muzzle of a gun looked

into our faces, and every word of command on board was distinctly

heard.

My clothing was perforated with bullets as I stood in the bow, the

heel-jigger in my right hand and the exploding-line in the left. We

were near enough then, and I ordered the boom lowered until the

forward motion of the launch carried the torpedo under the ram’s

overhang. A strong pull of the detaching-line, a moment’s waiting

for the torpedo to rise under the hull, and I hauled in the left

hand, just cut by a bullet.

The explosion took place at the same instant that 10 pounds of grape,

at 10 feet range, crashed in our midst, and the dense mass of water

thrown out by the torpedo came down with choking weight upon us.1

A. F. Warley, the captain of the Albermarle, had thought his

position weak, as the guns on land were of little use, and they were

under constant surveillance from the other side of the river.

Nevertheless, he respected the Federals for their attack, and said,

“a more gallant thing was not done during the war.”2

Cushing continued his story:

Twice refusing to surrender, I commanded the men to save themselves;

and throwing off sword, revolver, shoes, and coat, struck out from my

disabled and sinking boat into the river. It was cold, long after the

frosts, and the water chilled the blood, while the whole surface of

the stream was plowed up by grape and musketry, and my nearest

friends, the fleet, were twelve miles away, but anything was better

than to fall into rebel hands. Death was better than surrender. I

swam for the opposite shore, but as I neared it a man, one of my

crew, gave a great gurgling yell and went down.

The rebels were out in boats, picking up my men; and one of these,

attracted by the sound, pulled in my direction. I heard my own name

mentioned, but was not seen. I now “struck out” down the stream,

and was soon far enough away to attempt landing. …

Again alone upon the water, I directed my course towards the town

side of the river, not making much headway, as my strokes were now

very feeble, my clothes being soaked and heavy, and little chop-seas

splashing with a choking persistence into my mouth every time that I

gasped for breath. Still, there was a determination not to sink, a

will not to give up; and I kept up a sort of mechanical motion long

after my bodily force was in fact expended.

At last, and not a moment too soon, I touched the soft mud, and in

the excitement of the first shock I half raised my body and made one

step forward; then fell, and remained half in the mud and half in the

water until daylight, unable even to crawl on hands and knees, nearly

frozen, with brain in a whirl, but with one thing strong in me—the

fixed determination to escape. The prospect of drowning, starvation,

death in the swamps—all seemed lesser evils than that of surrender.

As day dawned, I found myself in a point of swamp that enters the

suburbs of Plymouth, and not forty yards from one of the forts. The

sun came our bright and warm, proving a most cheering visitant, and

giving me back a good portion of the strength of which I had been

deprived before. Its light showed me the town swarming with soldiers

and sailors, who moved about excitedly, as if angry at some sudden

shock. It was a source of satisfaction to me to know that I had

pulled the wire that had set all these figures moving (in a manner

quite as interesting a the best of theatricals), but as I had no

desire of being discovered by any of the rebs who were so plentiful

around me, I did not long remain a spectator. My first object was to

get into a dry fringe of rushes that edged the swamp; but to do this

required me to pass over thirty or forty feet of open ground, right

under the eye of the sentinel who walked the parapet.

Watching until he turned for a moment, I made a dash to cross the

space, but was only half-way over when he turned, and forced me to

drop down right between two paths, and almost entirely unshielded.

Perhaps I was unobserved because of the mud that covered me, and made

me blend in with the earth; at all events the soldier continued his

tramp for some time.... I [regained the swamp] by sinking my heels

and elbows into the earth and forcing my body, inch by inch, towards

it. For five hours them, with bare feet, head, and hands, I made my

way where I venture to say none ever did before, until I came at last

to a clear place, where I might rest upon solid ground. The cypress

swamp was a network of thorns and briers, that cut into the flesh at

every step like knives, and frequently, when the soft mire would not

bear my weight, I was forced to throw my body upon it at length, and

haul it along by the arms. Hands and feet were raw when I reached the

clearing, and yet my difficulties were but commenced. A working-party

of soldiers was in the opening, engaged in sinking some schooners in

the river to obstruct the channel. I passed twenty yards in their

rear through a corn furrow, and gained some woods below. …

I went on again, and plunged into a swamp so thick that I had only

the sun for a guide and could not see ten feet in advance. About 2

o’clock in the afternoon I came out from the dense mass of reeds

upon the bank of one of the deep narrow streams that abound there,

and right opposite to the only road in the vicinity. It seemed

providential that I should come just there, for, thirty yards above

or below, I never should have seen the road, and might have struggled

on until worn out and starved—found a never-to-be-discovered grave.

As it was, my fortune had led me to where a picket party of seven

soldieries were posted, having a little flat-bottomed, square-ended

skiff toggled to the root of a cypress tree that squirmed like a

snake into the inky water. Watching them until they went back a few

yards to eat, I crept into the stream and swam over, keeping the big

tree between myself and them, and making for the skiff.

Gaining the bank, I quietly cast loose the boat and floated behind it

some thirty yards around the first bend, where I got in and paddled

away as only a man could where liberty was at stake.

Hour after hour I paddled, never ceasing for a moment, first on one

side, then on the other, while sunshine passed into twilight, and

that was swallowed up in thick darkness, only relieved by the few

faint star rays that penetrated the heavy swamp curtain on either

side. At last I reached the mouth of the Roanoke, and found the open

sound before me.

My frail boat could not have lived a moment in the ordinary sea

there, but it chanced to be very calm, leaving only a slight swell,

which was, however, sufficient to influence my boat, so that I was

forced to paddle all upon one side to keep her on the intended

course.

After steering by a star for perhaps two hours for where I thought

the fleet might be, I at length discovered one of the vessels, and

after a long time got within hail. My “Ship ahoy!” was given with

the last of my strength, and I fell powerless with a splash into the

water in the bottom of the boat, and awaited results. I had paddled

every minute for ten successive hours, and for four my body had been

“asleep,” with the exception of my two arms and brain. The picket

vessel Valley City—for it was she—upon hearing the hail at

once slipped her cable and got underway, at the same time lowering

boats and taking precautions against torpedoes.

It was some time before they would pick me up, being convinced that I

was the rebel conductor of an infernal machine, and that Lieutenant

Cushing had died the night before. …

I again received the congratulations of the Navy Department, and the

thanks of Congress, and was also promoted to the rank of

Lieutenant-Commander.3

1. “The

Destruction of the 'Albermarle'” by William Cushing in The

Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine: May 1888 to

October 1888 (New York: The

Century Co., 1888) p. 432-436.

2. “Note

on the Destruction of the 'Albemarle'” by W. F. Warley in The

Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine, p. 439-440.

3. “The

Destruction of the 'Albermarle'” by William Cushing in The

Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine

p. 436-438.