Having decided to

move to Spotsylvania, Grant's men continued to march in that

direction on the night of May 7th. At the front Sheridan's

cavalry had to clear the road of Confederate cavalry. Lee was not

certain where Grant was going, but ordered Richard Anderson, who had

taken over Longstreet's corps, to move in the direction of

Spotsylvania. He did not tell him the movement was urgent, but

Anderson moved early, at 10 pm on May 7th, to escape the

stinking bodies and burning forest on the Wilderness battlefield.

Early

on May 8th,

150 years ago today, the Federal cavalry renewed their efforts to

clear the road to Spotsylvania. Fitzhugh Lee's men, after a gallant

stand, withdrew from their barricades and took up a new position on

Laurel Hill, just northwest of Spotsylvania. He sent for

Anderson to help, and

at

this point the Confederates' early movement paid off. Before long

infantry were flying into the cavalry positions, just as Warren's V

Corps arrived to attack. Warren did not know that the Confederates

had infantry on the field, and ordered his troops to press forward.

The men were tired and hungry from their long march, but Warren

shouted, “Never mind the cannon! Never mind the

bullets! Press on and clear this road! It’s the only way to get

your rations!" The Federals charged, but at 60 yards the

Confederates unleashed volley after volley. The bluecoats fell back

and tried again, but again they were beaten back. Warren, seeing more

Confederate infantry arriving, halted his attacks and told Meade of

the situation.

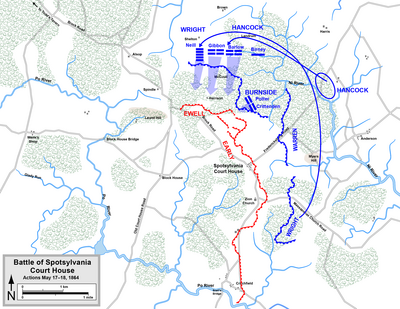

|

| Lines at Spotsylvania |

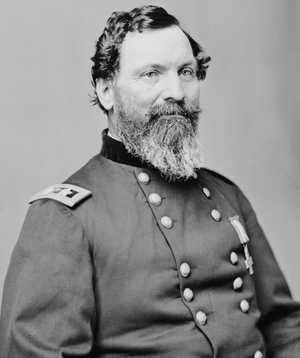

Meade could not believe that

the Confederates had arrived on the field so soon. He ordered John

Sedgwick to join Warren and continue the attacks. Much time was spent

in preparing the lines, and by the time they advanced at 6 pm,

Ewell's Corps had joined Anderson's on the battlefield. The Federal

assault was a disaster. Orders were confused, units lost their way,

and only one division and one brigade ended up attacking. This weak

force had no chance of breaking the Confederate line, and the

Federals were soon broken.

They day had been a

provident success for the Southerners. The Federal movement had been

detected, and infantry was on hand to meet it. They had won the race

for Spotsylvaia, and the attack which the Union had spent so long

planning turned out to be an embarrassing failure.

.png/450px-Battle_of_Spottsylvania_(1).png)