While Sheridan was

out on raiding the Virginia Central Railroad, and trying to attract

the attention of Robert E. Lee. Grant and Meade began to put their

plan to attack Petersburg into action. The movement began on the

night of June 12, and work began on an over 2000 foot pontoon bridge

across the James River. The Union army began crossing on June 14, and

all the men were not across until the 18th. However, they

did not wait that long to strike at Petersburg. The advance on that

town began on June 15. Leading the Federal army was Benjamin Butler's

Army of the James, which had already failed to capture Petersburg

once during the Bermuda Hundred Campaign.

Petersburg was

very weakly held. Lee had not realized that Grant was attacking

Petersburg with his entire army, and so remained north of the James.

The commander at Petersburg was P. G. T. Beauregard. He still had to

deal with Butler on the Bermuda Hundred, so he only had 2,200 men to

hold the Petersburg defenses.

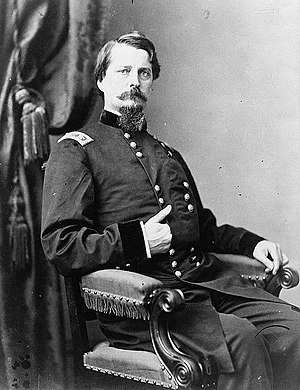

|

| Smith |

As “Baldy”

Smith, commander of the XVIII corps, approached Petersburg on June

15th, 150 years ago today, he was worried about the

strength of its entrenchments. There were six foot high breastworks

surrounded by a ditch six feet deep and fifteen wide. In front of

this obstacle was a row of felled trees with branches sharpened to

delay the attackers while they were shot at from the walls. Smith

spent time examining the positions, and looking for weak spots. By 4

pm he had decided to attack with heavy skirmish lines, hoping that

they would not suffer heavily from Confederate fire during the

charge. He set the launch off time at 5 pm, but it was discovered

that no one had told the artillery chief of the plans. The guns were

needed for supporting fire while the infantry attacked. The artillery

horses had been sent away for water, and could not pull the guns into

position. Smith delayed the attack until 7 pm, when his troops were

able to move forward.

When Smith's men

charged these works, they found them much less formidable than they

had imagined. As they pushed backed the skirmishers, crossed the

abatis and climbed the ditch, they quickly gained the walls meeting

little resistance. Many batteries were captured by Smith's advance

over more than a mile of entrenchments. At this point, however, Smith

halted the assault. The Confederates fell back to a weaker line, and

Smith thought it likely that Lee had crossed the James and was in his

front. He wanted to prepare his men to meet a counter-attack, not

continue forward. Winfield Scott Hancock arrived, ahead of his corps,

and although the senior officer on the field and normally aggressive,

he acquiesced to Smith's decision. No more attacks would be made that

night.

|

| Hancock |