|

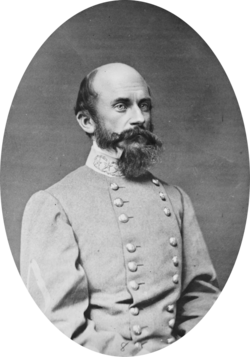

| Bragg |

Retreating from the invasion of Kentucky in the fall of 1862, Braxton Bragg pulled back his army to Murfreesboro, Tennessee, eventually taking up a defensive position along Stone's River. His opponent, Don Carlos Buell, was too slow for Abraham Lincoln's liking, so he replaced him with Major General William S. Rosecrans, who had recently won success in the battles of Iuka and Corinth. Although it was clear that the War Department required action from him, he took his time reorganizing his army, and set out towards Bragg on December 26th. The Confederates had launched a cavalry raid under John Hunt Morgan on Union supply lines, and although the raids would impact other armies, such as that of U.S. Grant moving on Vicksburg, Rosecrans continued his movement.

|

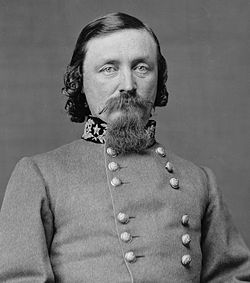

| Rosecrans |

Rosecrans arrived in Murfreesboro on December 29th. He had about 41,000 to Bragg's 35,000. However, the forces were closer than that might appear. Bragg's cavalry under Wheeler was very effective, they day before having ridden around Rosecrans, capturing wagons and prisoners. Bragg also cooperated with detached cavalry forces under Morgan and Forrest. Rosecran's cavalry forces on the other hand were very weak.

|

| Rosecrans at Stone's River |

On December 30th, the Union army moved into its lines. The armies were positioned on parallel lines four miles long. Although the Federals did not know it because of the good service of the Confederate cavalry, Bragg's left flank was very weak. So instead he decided to attack the Confederate right and capture the heights across the river, which would give him a good artillery position to bombard the rest of the rebel line. Bragg decided on a similar plan – to strike the Union right. As at the First Battle of Bull Run, the advantage would go to whoever struck first. It was the commanders that made the difference in this battle. Bragg ordered his men to attack at dawn, Rosecrans had his men wait until after breakfast.

|

| Hardee's Attack |

At dawn on December 31st, 150 years ago today, the Confederates struck. The 10,000 men of William Hardee's corps struck Union general Richard Johnson's division before they had finished breakfast. As the attack rolled forward, a gap developed in the Confederate line, but it was seamlessly filled by Patrick Cleburne's division. The Union put up a fierce resistance, Johnson's division suffering 50% casualties, but none the less they were driven back three miles. Realizing his army was near disaster, Rosecrans canceled his planned attack. He rode along his lines, covered in the blood of Col. Julius Garesche, who had been beheaded by a cannonball at his chief’s side.

As Hardee's successful attack began to slow, Polk's corps moved forward in a second wave. They encountered serious resistance from Major General Philip Sheridan, who had anticipated an early attack and had his troops ready to meet it. In his area of the Union front was what was called the Slaughter Pen. Fighting continued for four hours before the Confederates finally prevailed. At 11 am, with ammunition running low, Sheridan pulled his division back. He had done well, but his troops had suffered terribly. All the brigade commanders, and one third of the men, had fallen in their defense.

|

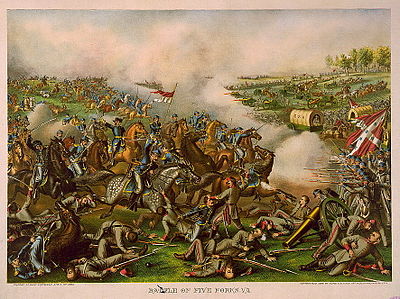

| Hell's Half Acre |

In the five hours after their attack had began the Confederates had been successful – having driven back the Union lines and captured 28 guns and over 3,000 prisoners. The Union position now hinged on what was called Round Forrest by the locals, a wooded area filled with rock formations, which this day would gain the name Hell's Half Acre. As the Union line was stabilized by the leadership of Rosecrans and others, the Federals beat back Confederate attacks along the line.

To complete his victory, Bragg would need more troops. He ordered Breckenridge on the right to move to make this attack. Breckenridge, however, refused. He thought he was facing a large Union force, but they had actually retreated because of the Confederate attacks. When he finally moved forward, he was embarrassed to find the area to his front barren of opposition. When he finally did attack, it was in a piecemeal manner that the Federals were able to repulse. Another attack was tried and it too failed. The battle was over by 4:30 pm.

|

| Breckenridge's Attack |

Bragg was convinced he had won a great victory. He telegraphed to Richmond that night,

The enemy has yielded his strong position and is falling back. We occupy [the] whole field and shall follow him. General Wheeler with his cavalry made a complete circuit of their army on the 30th and 31st; captured and destroyed 300 wagons loaded with baggage and commissary stores; paroled 700 prisoners. He is again behind them and captured and ordnance train to-day. We secured several thousand stand small-arms. ... God has granted us a happy New Year.

However, his victory was not as sure as he thought. Instead of cutting the Union supply line, the Nashville Pike, the attacks had actually concentrated Federals closer around that point as they fell back under Confederate pressure.

|

| Thomas |

Across the field Rosecrans was holding a council of war to determine what should be done. At first he was inclined to withdraw, but he was convinced otherwise by Gen. George Thomas, later known as the “Rock of Chickamauga,” who said that night, “This army does not retreat!” They did not, and the bloody fighting would continue the next days.