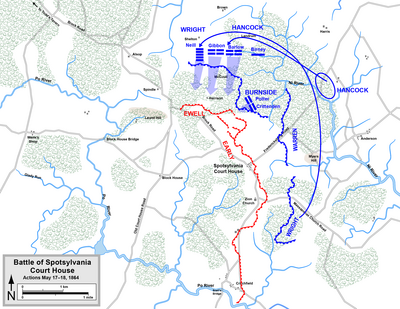

When the armies of

Grant and Lee again came to a halt in the entrenchments south of the

North Anna River, Grant decided to move again. He would again move

south east, trying to get around Lee's flank, keep close to the navy,

and edge toward Butler's army on the Bermuda Hundred. The army

successfully withdrew from their lines on the night of May 26,

recrossing the North Anna and then turning the columns to march down

stream. When Lee discovered the movement, he set his troops in motion

in the same direction. He chose a good defensive position behind

Totopotomy Creek, just a few miles north of Richmond. He was not,

however, sure of what the Federal plans were, so he sent Wade

Hampton's cavalry forward to reconnoiter.

|

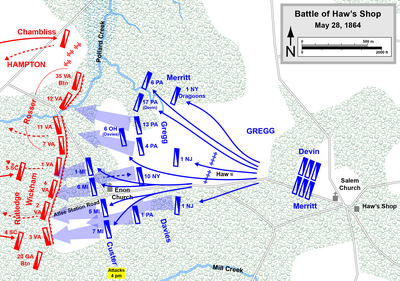

| Battle of Haw's Shop |

Hampton met the

Federal in a sharp engagement on May 28th at the Battle of

Haw's Shop. There were about four thousand troopers on both sides,

and the battle involved the Federals trying to dislodge the

Southerners, who had dismounted and arrayed behind hastily build

breastworks. After repulsing several attacks over seven hours,

Hampton pulled his men back. They had fulfilled their mission, having

learned that two crops had crossed the river. This was the largest

cavalry battle in the east in nearly a year, but it was different

than those which had gone before, as it was fought behind

breastworks.

The next day Grant

and Meade's army continued to push forward, and took up a position

opposite Lee across Totopotomoy Creek. On 30th the

Federals pressed Lee's lines. Meanwhile, Lee ordered Early to strike

the Federal left flank. Robert Rodes successfully reached the flank

and crushed the division placed there. But the attack stalled, and

Early's other divisions were not able to provide adequate support.

Stephen Ramseur, a new division commander, made a rash attack that

was repulsed by the Federal artillery. At length Early called of the

attacks.

Lee was

disappointed to hear of Early's failure, but he was even more

disturbed by another piece of news that he received – that a corps

was being sent by Butler from the Bermuda Hundred to reinforce Grant.

He needed to ensure that Grant did not use these troops to outflank

him, so he ordered Fitzhugh Lee to scout with his cavalry out on the

Confederate right. Lee's men rode towards Cold Harbor, where the next

great battle of the Overland Campaign was destined to occur.

.png/450px-Battle_of_Spottsylvania_(1).png)