At around 1 pm George Meade resumed his advance toward the Confederate left, held by Stonewall Jackson. Jackson's men were ready for them, hidden along the wooded ridge. However, they did not know their position had a fundamental flaw. A. P. Hill's division held the front line, but a wooded, boggy section of the line between Archer and Lane was left unguarded. It was thought that the bog was impassable for infantry. However, the Federals soon proved that wrong. Meade's division pushed forward towards the gap, at first faltering upon encountering artillery fire and ditch fences which were dug to keep out animals. As the men struggled through these obstacles they were encouraged by their commander, George Meade, a West Point engineer with significant combat experience. On the Confederate side, James Archer, seeing the Federal advance, realized the Yankees were heading straight for the gap in the line. He threw one of his regiments into the gap, and sent back to the rear to call up another brigade of reinforcements.

|

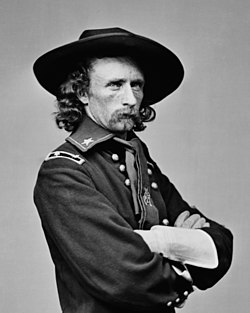

| Meade |

Meade's first brigade rushed through the gap, climbing over a railroad embankment and turning to the right, struck Lane's brigade on the flank. The third Union brigade turned to the left, striking Archer. The second rushed in as well, supporting the other two. Archer and Lane's lines bent back under the heavy pressure on their flanks, but were not broken. Maxey Gregg's Confederate brigade was a little to the rear of the Confederate line. They were called up as reinforcements, but did not know exactly where to go. They lay down under artillery fire and stacked their muskets. Hearing musketry fire rolling towards them, they began to reform, but before they could even grab their rifles the Federals were upon them. Unprepared for the fierce attack by Meade's advancing men, the Southerners fled. Gregg, who was partially deaf, did not hear the Federals and was shot from his horse. The bullet cut his spinal cord and he died two days later.

Although the Confederate line had been pierced by Meade, there was a second line. The divisions of Jubal Early and William Taliaferro advanced forward to seal the gap. Lane and Archer's men rallied and poured their fire into Meade. Hit from three sides with no reinforcements arriving, the Federals could not hold. They abandoned the ground that they had gained and fell back. One of the brigade commanders was killed and another wounded, along with many of the men, and the formations were scattered and confused.

|

| Gibbon |

As Meade's division was recoiling from its defeat, John Gibbon was preparing to go forward on Meade's right. At 1:30 pm this division moved forward, but by that time it was too late to follow up on Meade's temporary success. Gibbon's moved across open fields toward the enemy, taking heavy casualties from the Confederates on the wooded hill. As they grew closer Gibbon halted his men, exchanging fire with the Confederates. Finally he ordered a charge.

|

| Slaughter Pen Farm |

They hit the Confederates positioned along a railroad cut, a ready-made defense. The Confederate line held firm, and after the rifles were fired, both sides resorted to hard hand-to-hand fighting with bayonets and clubbed muskets. After a bitter fight the Confederates finally broke. However, Gibbon did not long remain in position in peace. The Confederates rallied and counter attacked. Gibbon's men were out of ammunition, and with more hand-to-hand fighting the Confederates were able to recapture the railroad cut. The Federals fell back, having been unable to hold on without reinforcements. Gibbon wasn't done trying however. He launched three more attacks, but was unable to gain any more success. After the fourth failure, he realized that without more troops, he could gain nothing but casualties.

Gibbon and Meade and been unsuccessful primarily because their initial gains were not supported with reinforcements. It was not for lack of men. Meade, coming back from his defeat, encountered David Birney with his division, and poured forth a slew of profanities at him for failing to move forward. The problem was not just with the lower echelons of command. Burnside ordered Franklin to continue his attacks, but Franklin refused saying all of his troops were already in action. However, this was not true. 5,000 Northerners had fallen as had 4,000 Confederates, but he still had 20,000 men available that had not fired a shot. This ended the battle on the Confederate right, and with it ended the Northern chance for victory at Fredericksburg.

It was this section of the field that the Federals had their best chance. They achieved a breakthrough, but troops were not available to make good that success. Franklin's refusal to attack doomed the battle for the Union. George Meade said:

For my part the more I think of that battle the more annoyed I am that such a great chance should have failed me. The slightest straw almost would have kept the tide in our favor.