|

| Federal entrenchments |

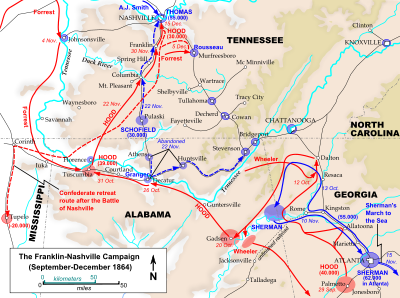

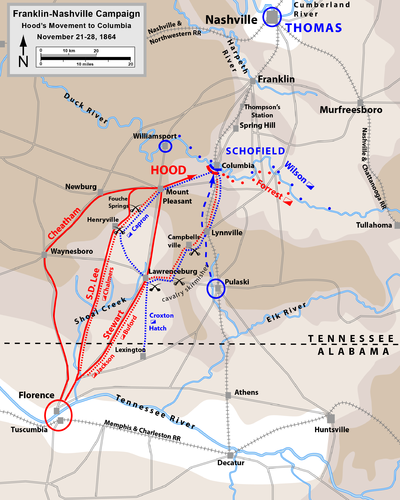

On the morning of December 16th, 150 years ago today, the Federal troops outside Nashville prepared to attack John Bell Hood's new position. It was much shorter and stronger than the previous day's, and the flanks were secured to prevent a repetition of the previous day's disaster. However, they did have critical weaknesses. On Shy's Hill, some of the highest ground on the Confederate left, the entrenchments were on the actual crest of the hill rather than the military crest, a little lower. This meant that the attacking Federals would, for a time, be hidden from Confederate shot as they charged up the hill. Thomas's plan from the previous day remained unchanged – to feint on the right and then push hard on the rebel left.

Unlike the previous day, the diversionary attack did convince Hood to shift forces away from the truly threatened point. Four brigades attacked the right around 3 pm. Most were turned back by the heavy Confederate fire, but the 13th United States Colored Troops continued to pressed forward. They charged up to the Confederate parapets before being driven back, losing a flag and 40% of their strength in the process. Cheatham, commanding the corps on the Confederate left, had to stretch his line even thinner to protect the flank and rear from Union cavalry incursions.

|

| McArthur |

With this golden opportunity on the Confederate right, the Federals failed to move. John Schofield was ordered to make the attack with his corps, but he believed he was outnumbered and requested reinforcements. When these arrived, he still did nothing. With sunset not far distant, Brigadier General John McArthur decided to take matters into his own hands. He announced to his commanders that his division would attack in five minutes unless he received orders to the contrary. No orders arrived, and so his three brigades moved out toward the Confederate left on Shy's Hill. His attack was very successful. The misplacement of the entrenchments meant that the hill could be captured without much difficultly, and another brigade was so close on the heels of the Confederate skirmishers that they entered the rebel works with them. One Federal officers wrote:

It was more like a scene in a spectacular drama than a real incident in war. The hillside in front, still green, dotted with boys in blue swarming up the slope; the wavering flags; the smoke slowly rising through the leafless tree-tops and drifting across the valleys; the wonderful outburst of musketry; the ecstatic cheers; the multitude racing for life down in the valley below …. As soon as the other divisions farther to the left saw and heard the doings on their right, they did not wait for orders. Everywhere, by a common impulse, they charged the works in front, and carried them in a twinkling.

With the left crushed, much of Hood's army fell apart. Sam Watkins of the 1st Tennessee wrote:

Such a scene I never saw. The army was panic-stricken. The woods everywhere were full of running soldiers. Our officers were crying, 'Halt! Halt!' and trying to rally and re-form their broken ranks. The Federals would dash their cavalry in amongst us, and ever their cannon joined in the charge. … Wagon trains, cannon, artillery, cavalry, and infantry were all blended in inextricable confusion.

Through the night of December 16th the Confederates retreated, with part of Lee's corps still intact and serving as rearguard and repelling strikes by Union cavalry. Over the next few days the rebels pushed forward into Alabama. The Union infantry could make little pursuit due to a missing pontoon train, and two newly arrived divisions of Confederate cavalry under Nathan Bedford Forrest handled the attacks of the Federal troopers.

|

| USCT monument at the Nashville Cemetery. Source. |

In this battle the Federals lost around 387 killed, 2,562 wounded, and 112 missing. The Confederate casualties are harder to pin down, but they probably lost around 2,500 killed and wounded and more than 4,500 prisoners. This battle was the deathnell of Hood's Army of the Tennessee. They had entered Tennessee with 38,000 men. When they returned to the safety of Alabama they had about 15,000 men. Much of the blame for this debacle was due to John Bell Hood, who had wasted his army in bloody frontal attacks, and had continued to press on in the invasion against vastly superior Federal forces. He resigned his command in January, and the shattered remnants of his command were integrated into other forces.