|

| Entrenchments at Petersburg |

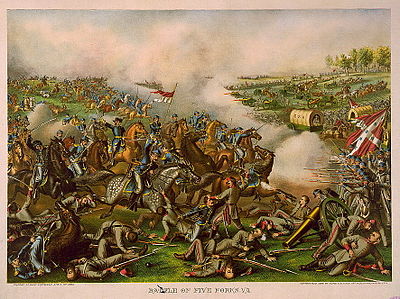

When Ulysses S. Grant received news of Phil Sheridan's victory at Five Forks the previous day, he immediately gave orders for a general attack to be made on Lee's lines at Petersburg. This opportunity coincided with a major attack Grant had been planning for some time. For months the Confederates had been stretched thinner and thinner, and now they must surely be planning to evacuate the position, since Sheridan could cut off their lines of communication. Grant wanted to strike and destroy Lee before he escaped.

|

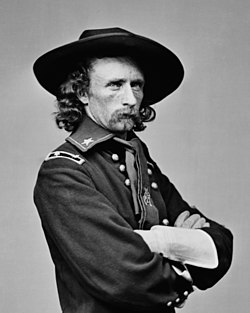

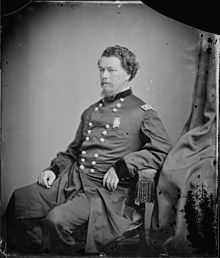

| Horatio Wright |

The assault was preceded by an artillery barrage which began at 10 pm on April 1st, and continued for some four hours. Not longer after, in the early morning of April 2, the Union infantry attacked. The attack was begun by Horatio Wright's VI Corps, which was facing some of A. P. Hill's about in the center of the battle lines. Wright had carefully chosen the point to attack, on the far left of his position, where the lines were close together and these were few obstacles in between. He had a vast superiority of numbers, and was able to bring 14,000 troops to bear on a mile long line held by only 2,000 Confederates. However, the southerner's works were high and strong, and they had well sited cannon posted along the line.

At 4:40 two Union cannon fired, signalling the beginning of the attack. The Federal troops moved forward, preceded by pioneers to clear away the wooden obstructions in front of the Confederate lines. The Confederate pickets were driven back, but they alerted the main line of the attack, and soon the Yankees began to receive a heavy and well-directed fire. The first Federal over the wall was Captain Charles Gould of the 5th Vermont. He ran down the path made by the Confederate pickets, followed by three men with the rest not far behind, and crossed the ditch on a plank bridge the Confederate had placed there. Gould quickly climbed over the wall and gained the parapet, but the rebels on the other side were ready for him. He was immediately cut three times by bayonets and swords, and one southerner pointed a rifle directly at him and pulled the trigger, but the gun misfired. He was pulled back over the parapet by Corporal Henry Rector, and before long more Union troops arrived and secured the position.

All along the line Federals climbed up the works, capturing them with quick hand-to-hand fighting. Breaches formed in the Confederate position and soon it fell entirely into Federal hands. The 2nd Rhode Island captured six Confederate cannon, and then quickly turned them on their former owners to drive back a counter attack.

|

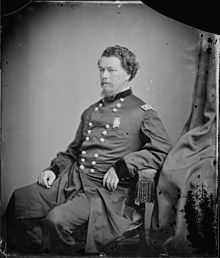

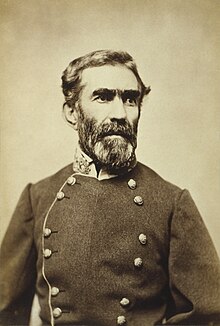

| A. P. Hill |

After this initial success, Wright's troops continued to push forward in ragged order, capturing the Southside Railroad a mile in the rear. This would not be a temporary success, like Gordon had won at Fort Steadman. Instead it was a major breakthrough. A. P. Hill, the Confederate corps commander, worked to organize a resistance to meet this major reverse. He was riding through the woods towards Harry Heth's headquarters, accompanied by only one staff officer. The Confederate officers encountered two Union stragglers of the 138th Pennsylvania, Corp. John Mauk and Private David Wolford. Hill demanded their surrender, but instead Mauk fired, killing Hill. He was one of the highest ranking Confederate killed during the war.

|

| The attacks |

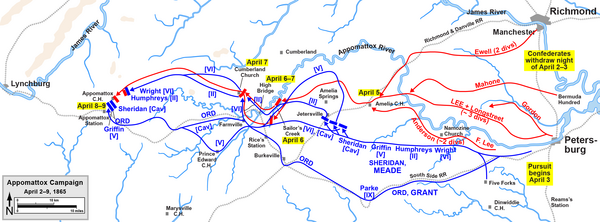

Wright reorganized his corps, and began widening the gap formed in the Confederate line, with support from Gibbon's XXIV Corps. At 6:00 Humphreys' II Corps on the left attack, and also made progress. Many Confederates resisted just to buy time, hoping that reinforcements would arrive. Fort Gregg was stoutly defended, and the attackers got stuck in the ditch, which was filled with mud and water. However, after several attacks, Union soldiers were able to work their way around to the fort's rear, drive off the few defenders placed there, and gain entrance into the fort.

|

| Dead Confederate at Petersburg |

Robert E. Lee realized that he could not maintain his lines, and that Richmond and Petersburg must fall. He telegraphed the Secretary of War:

I see no prospect of doing more than holding our position here until night. I am not certain I can do that. If I can I shall withdraw to-night north of the Appomattox, and, if possible, it will be better to withdraw the whole line to-night from James River. I advise that all preparations be made for leaving Richmond tonight.

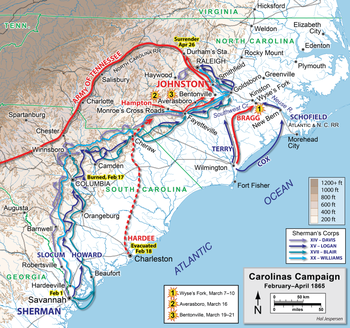

During the day of heavy fighting along the entire line, Grant's army lost about 4,000 men, the Confederates about 5,000 men, mostly captured.Lee's men began evacuating the lines which they

still retained at 8:00 pm. The government abandoned Richmond that

night, taking with them what papers they could. The retreating

soldiers set fire to the warehouses, and other structures of military

use. The fire spread out of control, and much of the city burnt to

the ground.

.jpg/400px-Currier_and_Ives_-_The_Fall_of_Richmond%2C_Va._on_the_Night_of_April_2d._1865_(cropped).jpg) |

| Richmond burning |

That night Grant wrote to his wife:

I am now writing from far inside of what was the rebel fortifications this morning but what are ours now. They are exceedingly strong and I wonder at the sucsess [sic] of our troops carrying them by storm. But they did it and without any great loss. Altogether this has been one of the greatest victories of the war.

Early the next morning, Union troops found that Lee had abandoned his lines. He had set off towards Appomattox. The last stage of the American Civil War had begun.

|

| The ruins of Richmond after the fire |

.jpg/400px-Currier_and_Ives_-_The_Fall_of_Richmond%2C_Va._on_the_Night_of_April_2d._1865_(cropped).jpg)

.jpg/250px-John_Newton_(ACW).jpg)