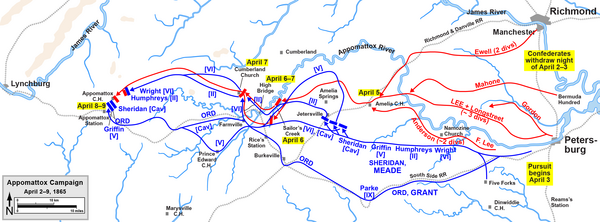

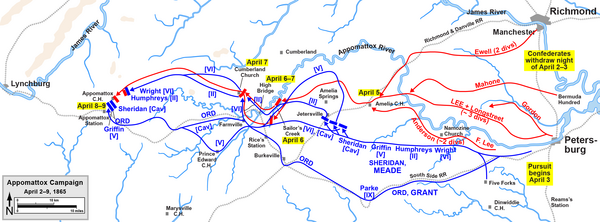

When Grant broke his lines around Petersburg on April 2nd and Lee put his army into retreat, his plan was to keep ahead of the Federals and join Joseph Johnston's army in North Carolina. He was very low on supplies, so he would have to resupply his army along the way. He pushed his men hard to make it to the supplies that were supposed to be waiting for him at Amelia Court House. When he arrived there on April 4th, his exhausted men having marched day and night, he found that ammunition had been sent from Richmond instead of food. The little that had been traveled by wagons had been captured by Phil Sheridan's cavalry which had been hard on the Confederate heels. The rebels couldn't eat gunpowder, so Lee had to halt his army for a day to forage for what supplies they could find in the countryside, allowing Grant to catch up. Lee continued to push his army forward, but his prospects grew darker and darker. The Federal cavalry was pressing at the army's heels, but Lee did not have the time or strength to halt to beat them back.

|

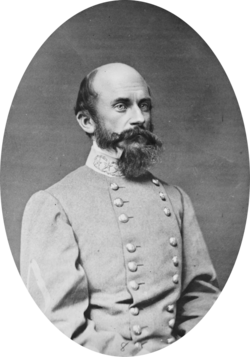

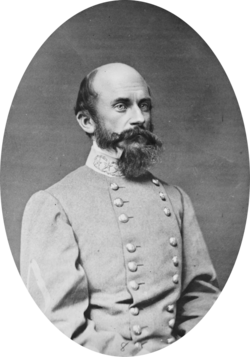

| Ewell, who was captured at Sailor's Creek |

On April 6th disaster struck in what is called the Battle of Sailor's Creek. Some Confederates were delayed in their march by having to fend of the pursuing Federals, and so a gap developed in the Confederate column. Eventually the corps of Anderson and Ewell were separated and brought to bay. Surrounded by Grant's army, their men were either captured or scattered. When he saw the broken remnants of Anderson's corps fleeing the field, Lee exclaimed, “My God, has the army dissolved?” “No General,” Major General William Mahone replied, “here are troops ready to do their duty.” Lee had to keep moving.

The rebels were headed for Appomattox Station, where they could get the supplies they desperately needed. But on April 8th Union cavalry arrived there first, and captured the food, foiling Lee's plans. The day before Grant had sent him a message suggesting he surrender. Lee refused, still hoping that he could reach Lynchburg, where more supplies waited.

|

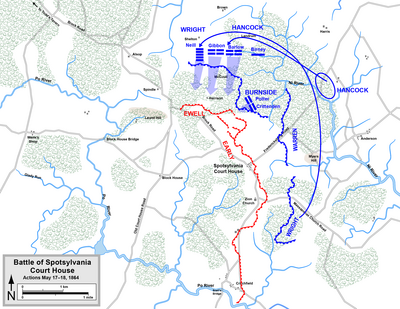

| Gordon |

On the morning of April 9th, 150 years ago today, the Confederate army was near the small crossroads of Appomattox Court House. The Union army was converging on them, but at the moment only Sheridan's cavalry stood in their way. John Gordon's Second Corps attacked the Federals and drove several lines back. But as they reached the top of the hill on which Sheridan's man had been placed, they saw before them two Federal corps in line of battle. Gordon, his men halted, told a staff officer:

Tell General Lee I have fought my corps to a frazzle, and I fear I can do nothing unless I am heavily supported by Longstreet's corps.

When Lee received this message, he said:

Then there is nothing left for me to do but to go and see General Grant and I would rather die a thousand deaths.

Out of food, exhausted from the long, hard marches, much of the army missing, and surrounded by Union forces, Lee decided with the agreement of most of his officers that it was time to surrender. Grant agreed to meet with him to discuss the terms.

|

| Appomattox |