After defeating Fremont yesterday at the battle of Cross Keys, Ewell's men set out at dawn to join Jackson. During the night a group of Confederate pioneers had built a bridge out of wagons and boards across the south river at Port Republic. They began crossing this bridge and moving out northwest from Port Republic towards Shields. Along the left side of the road were fields stretching to the south fork of the Shenandoah River. On the right of the road were the forested foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains. A few miles from town the Stonewall Brigade encountered three Union batteries on a 70 foot high hill called the Coaling. It was called that because they burned the hill's wood to make charcoal. It was a good artillery position, overlooking much of the area. Jackson realized that the Coaling was the key to the entire field. He sent two regiments of the Stonewall Brigade to move through the woods to flank the Coaling, while the Confederate artillery would engage the batteries on the Coaling as support. The Union cannon were in a much better position, and inflicted many casualties on the Southerners. One battery went in with 150 men and 6 guns and ended the battle with only 50 men and one working gun. Edward Moore, one of the cannoneers later wrote,

"Having gone about a mile, the enemy opened on us with artillery, their shells tearing by us with a most venomous whistle. Halted on the sides of the road, as we moved by, were the infantry of our brigade. ... Again our two Parrott guns were ordered forward. Turning out of the road to the left, we unlimbered and commenced firing. ... We were hotly engaged, shells bursting close around and pelting us with soft dirt as they struck the ground. ... The constant recoiling of our gun cut great furrows in the earth, which made it necessary to move several times to more solid ground. In these different positions which we occupied three of the enemy's shells passed between the wheels and under the axle of our gun, bursting at the trail."

However, the flanking troops encountered serious difficulties. The terrain was very difficult, and it took a long time for them to get into position. When they finally reached their goal, they opened a scattered firing on the Union batteries, driving away the gunners. But the Federals rallied and returned to the pieces, and poured round after round of canister into the woods. The Virginians, unable to stand up to the artillery fire, fell back and reported their reverse. Jackson would need more troops to capture the Coaling. He ordered Richard Taylor's Louisiana Brigade, which had won the day at Winchester, to move on the Coaling. The Confederate troops were very slow in coming up, as they were having trouble with the new bridge. It became unsteady after hundreds of men had crossed, and one many fell into the fast river. After seeing that, the soldiers would only cross one man at a time for fear of getting wet. Robert Lewis Dabney, Jackson's chief of staff, tried to get the column halted so that he could have the bridge repaired, but the troops' commanders refused to halt and pushed forward, one man at a time.

|

| Erastus B. Tyler |

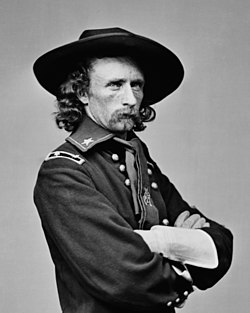

Meanwhile the Federal commander on the field, Erastus B. Tyler, was making a grievous mistake. He was commanding Shield's vanguard, but in deploying his troops he put them between the Coaling and the road, opposite the Confederate batteries and the majority of the Stonewall Brigade. He left the Coaling, which Jackson had recognized as the key position, weakly defended and open to being attacked on the flank.

|

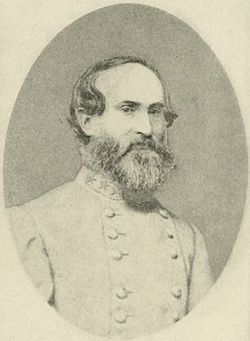

| Richard Taylor |

While Taylor was moving around the Union left flank, the Stonewall Brigade had to hold out on the plan. General Winder ordered his men to charge Tyler's line to gain as much time as possible. They set off with a cheer across a wheat field, and halting at a fence, opened fire on the Union infantry. They fought well and held their own against twice their number for half an hour. Finally the Federals charged and drove back the Confederates, who were running out of ammunition. The Confederates fled across the plain, pursued by cheering Northerners. Ewell, who had arrived with his first brigade, threw it in and was able to stop the Federal pursuit for the moment, but it could not hold for long.

Taylor was in position to attack the Coaling. He heard the cheers of the advancing Federals on the plain below, and realized that if he did not attack, a disaster might be coming with the army divided by a river crossed only by a rickety bridge. Therefore he ordered his men forward, and they charged the Coaling, giving out the Rebel yell. “On the Louisianians dashed,” one of them later wrote,

regardless of the terrific fire of the canister poured into their ranks by the battery.... its only effect is the accelerated the speed of the men in their impetuous charge. The nearer they approached the given point, of which the battery was the center, the less regard seemed paid to the preservation of the line, until finally the regiments became so intermingled as to present a disorganized, but formidable mass.

Taylor's men finally made it up the hill, and, after a brief hand to hand fight, drove back the Yankee gunners, capturing the hill and guns. But this success would not last long. The Federal infantry units in the area came forward and charged, driving back the victorious rebels. The Louisianians charged again and captured the position, but were driven back again by yet another counterattack. For the third time the Confederates came on again.

Panting like dogs-faces begrimed - nine-tenths of them bareheaded - the Federal wave rolls back over the guns, and now there is a grapple such as no other battle ever furnished. Men beat each other's brains out with muskets which they have no time to load. Those who go down to die think only of revenge, and they clutch the nearest foe with a grasp which death renders stronger.

The hill was won, and this time Taylor would hold it. They retained five of the six guns that were on the hill. The rest of the Union line soon crumbled with the key to the position lost and their cannon turned on themselves. The rest of Jackson's forces advanced with cheers, driving back Tyler's force for several miles.

Hearing of the defeat, Shield sent forward reinforcements, but they were too late. Fremont also failed to arrive in time to be of any use. He was delayed by Trimble, who was able to make it safely across the bridge, burning it behind him. Fremont was stranded on the other side, and could do nothing but shell the ambulances as they took the wounded off the field. Jackson had won a great victory. It was not just through his troops fighting on the battlefield, but his brilliant maneuvering, which had allowed him to strike two superior armies in turn, prevent them from uniting, and defeat them both. He was assisted in this by the failures of the Federal commanders, who were themselves scared of Jackson and had moved too slowly and cautiously to make use of their greatly superior numbers.

In these two battles, of Cross Keys and Port Republic, the Confederates lost 240 killed, 930 wounded and 100 missing or captured. The Federals lost 270 killed, 850 wounded and 780 captured.