|

| Cold Harbor |

The fighting between Lee and Grant shift next east again to Cold Harbor, a tiny town with great military significance as a junction of five roads. The Union cavalry captured the spot, and held it against Confederate attacks. Grant ordered Wright's XI corps to follow them in that direction. He knew that Lee would have to pass Cold Harbor if he was going to move, and Grant hoped to catch him on the road. Lee also was spoiling for a fight. He planned for Anderson's First Corps to join the cavalry, recapture Cold Harbor and ambush the Federal column on the march. Anderson arrived in the area before nightfall, and began pushing toward Cold Harbor before dawn on June 1st. He encountered the Union cavalry, and made his first serious attack around 8 am. The Union troopers held their fire until the Confederates were in close range, and then opened on them, quickly breaking up the attack with their rapid fire carbines. Another attack was launched, but it met the same fate. After this failure, the Confederate commanders became confused. Anderson did not press for the attacks to continue, and instead the men just remained where they were and dug. The offensive opportunity had been lost.

|

| Confederate entrenchments at Cold Harbor |

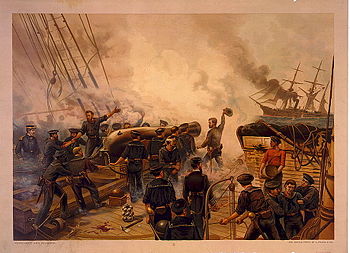

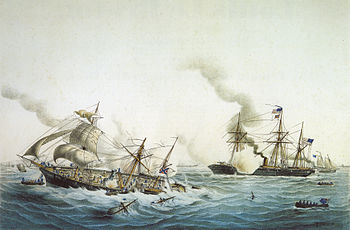

On the Yankee side, Wright's XI corps arrived at 1 pm and took over the line from the cavalry. Baldy Smith's XVIII corps which had been sent by Butler had been ordered to the wrong place, which meant they did not arrive at Cold Harbor until the afternoon. More time was spent planning the attack, and it was 6 pm by the time Wright and Smith were ready. Four Union divisions moved forward across the 1,200 yards that separated them from the Confederate line. They encountered formidable entrenchments, and from them artillery fire, and, as they advanced closer, a terrific small arms fire. The Federals were stopped cold all along the line, except at one point. Emory Upton, who had led a fairly successful attack on the Mule Shoe at Spotsylvania found the weak point in the Confederate line - an unguarded ravine. He pushed to within 70 yards of the Confederate position and was able to drive the Federal line back, capturing several hundred prisoners. But like at Spotsylvania, no more troops arrived to support him. The Confederates were able to maintain their lines until darkness, when Upton had to retire to his lines. Several thousand Federals were lost in this assault but only 600 Confederates.

Grant, however, saw opportunities. He ordered Hancock's II corps to Cold Harbor to renew the attack the next day. In their night march, they were led down the wrong road, which delayed their arrival time. When they did reach Cold Harbor the men were exhausted, and it was decided to delay the attack until the next day, June 3rd. Confederate reinforcements also arrived along with engineers who worked to improve the entrenchments and get the best fields of fire. At the ravine where Upton had gained success a new line was established to ensure the same thing did not happen again.

A light rain fell throughout the night, and the Union troops woke early to form for their attack. At 4:30 am, a signal round was fired, and an artillery bombardment was begun. For 10 minutes, shells were thrown into the Confederate works. Then the Yankee infantry jumped out of their works and went forward at the attack. Some Federals gained an initial success. Two of Hancock's brigades found a gap in the Confederate line, where a rebel commander had allowed his infantry to retire to a more pleasant camp. But along most of the line, the attacks met sheets of lead. One soldier wrote:

To give a description of this terrible charge is simply impossible, and few who were in the ranks ... will ever feel like attempting it. To those exposed to the full force and fury of that dreadful storm of lead and iron that met the charging column, it seemed more like a volcanic eruption than a battle, and was just about s destructive.... The men went down in rows, just as they had marched in the ranks, and so many at a time that many of the rear thought they were lying down.

The Confederates did not just fire from their trenches. They counter attacked in force, and sealed the gap that had been found in the line. Many Yankees were pinned down by the fire, and they tried to dig rifle pits with cups and bayonets. Based on some reports of a partial success, Meade ordered the attacks to be continued, but they were still not successful. Every Federal charge was beaten back with loss. At noon, Grant gave permission to Meade to call off the attack. The battle of Cold Harbor was over.

The Federals had suffered tremendous casualties. Thousands of men fell in a very short period, while Lee lost only 1,500. The wounded and dead lay on the field where many of the wounded were unable to crawl away. Grant delayed agreeing on a truce for several days, and by the time one was called several days later, it was too late for any of wounded to be saved. All who had not already been carried off had died on the field.

|

| Casualties of Cold Harbor |

The battle of Cold Harbor was costly for the Federal army. They lost about 1,844 killed, 9,077 wounded and 1,816 captured. The rebels too suffered significant casualties – 788 killed, 3,376 wounded and 1,123 captured. Grant later regretted the attack at Cold Harbor, as he wrote in his Memoirs.

I have always regretted that the last assault at Cold Harbor was ever made. I might say the same thing of the assault of the 22d of May, 1863, at Vicksburg. At Cold Harbor no advantage whatever was gained to compensate for the heavy loss we sustained. Indeed, the advantages other than those of relative losses, were on the Confederate side. Before that, the Army of Northern Virginia seemed to have acquired a wholesome regard for the courage, endurance, and soldierly qualities generally of the Army of the Potomac. They no longer wanted to fight them "one Confederate to five Yanks." Indeed, they seemed to have given up any idea of gaining any advantage of their antagonist in the open field. They had come to much prefer breastworks in their front to the Army of the Potomac. This charge seemed to revive their hopes temporarily; but it was of short duration. The effect upon the Army of the Potomac was the reverse. When we reached the James River, however, all effects of the battle of Cold Harbor seemed to have disappeared.