|

| Lincoln |

Throughout Lincoln's term as president there was significant resistance to him in the north. On one side there were the Radical Republicans who did not think Lincoln was firm enough on the issue of slavery, and on the other were the Democrats, some of whom even wanted immediate peace with the south. As the election of 1864 approached, it was clear that there would be obstacles in Lincoln's path for reelection. By the time of the election, the war had stretched on for nearly four bloody years, and there were many who did not think Lincoln was the man to end it.

|

| Frémont's campaign poster |

Early in the year Lincoln foiled plans from Salmon P. Chase, his Secretary of the Treasury, to become president. The Radical Republicans did nominate a candidate. At a convention in May, the “Radical Democrats,” as they called themselves, chose John C. Frémont, a former Union general. Frémont accepted the nomination, but offered to resign if Lincoln did not run for reelection. Lincoln did run, but Frémont dropped out anyway, in exchange for the resignation of Postmaster General Montgomery Blair, a Democrat.

|

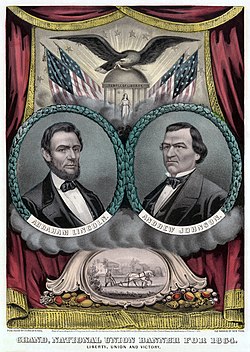

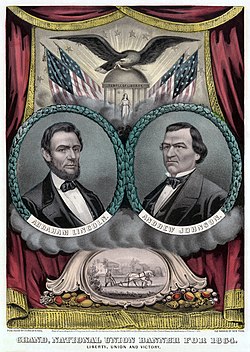

| Lincoln and Johnson |

Lincoln did not run again as a Republican. Instead his supporters held the National Union Convention, an alliance of the Republicans with some War Democrats. The idea was that they were putting aside politics, and instead focusing on winning the war. To strengthen the coalition, vice president Hannibal Hamlin, a Republican, was replaced with Andrew Johnson, the military governor of Tennessee and a Democrat.

The Democrats also ran a candidate, but their party was badly divided. Some wanted to continue fighting the war until the Union was reestablished, others wanted an immediate negotiated peace. This strife was evident in the results of the convention, held in Chicago. They nominated George B. McClellan, the general, for president, and George Pendleton, Representative from Ohio, for vice-president. The party platform was anti war, calling for immediate cessation of hostilities. But they had nominated McClellan, who was continuing the war.

|

| Cartoon of McClellan |

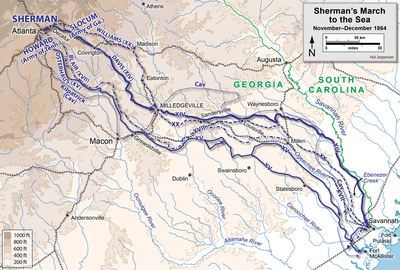

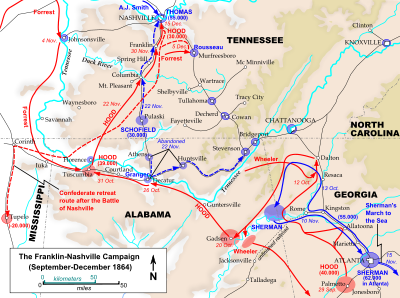

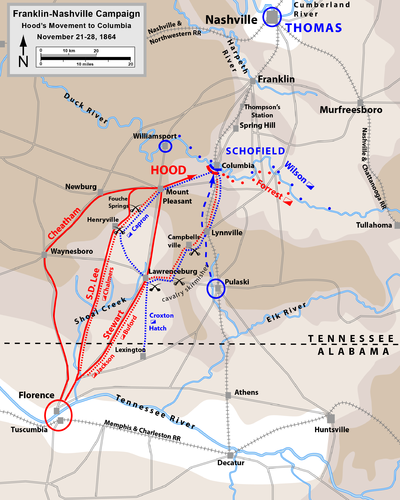

The division among the Democrats caused confusion in the advertising and propaganda during the campaign. The Republicans argued that McClellan's election would mean armistice, peace and despotism. Their motto was “Don't change horses in the middle of a stream,” trying to win the support of War Democrats so Lincoln could win the war. Early in the year, Lincoln did not believe that he could win reelection, and hoped to win the war before he would turn over the presidency. By November, the tide had turned. With the fall of Atlanta in September it seemed that the Union was winning battles, and that ultimate victory was in site.

|

| Republican campaign poster |

Although as the election approached things were looking up for Republicans, it was still far from a sure thing. Republicans worked to get Nevada's statehood approved at the eleventh hour, as they believed those votes would go to Lincoln. Congress had voted to allow Nevada to join back in March, along with Colorado and Nebraska, but before statehood could be finalized they needed to receive state constitutions adopted by popular conventions. Nebraska voted against becoming a state and Colorado did not adopt a Constitution. Nevada, however, passed a constitution, but the copies they sent to Washington did not arrive. Finally the governor decided to telegraph the constitution to Washington. It took two days to send the more than 16,000 words. This was the longest telegraph sent up to that point. The bill for the telegraph was $4,303.27 - more than $63,000 today. With the constitution sent in, Nevada was admitted to the Union on October 31. Just a week later, Lincoln carried the state in the election.

The election was held on November 8th, 150 years ago today. In an era before electronic vote counting or instant communication, election results could take weeks or months to arrive. But by the night of November 8th, enough counts had come in to be pretty certain that Lincoln would be reelected. The result turned out to be a Lincoln landslide. He won 212 electoral votes to McClellan's 21, loosing only New Jersey and Kentucky. The popular vote was significantly closer, with Lincoln winning 55% to McClellan's 45%. The Republicans also increased their majority in both the House and Senate. The voters had approved Lincoln's conduct of the war.

Late at night Lincoln gave a speech from the White House to a group of Pennsylvanians who were serenading him with a band. He said:

[A]ll who nave labored to-day in behalf of the Union organization have wrought for the best interests of their country and the world, not only for the present, but for all future ages. I am thankful to God for this approval of the people. … I do not impugn the motives of any one opposed to me. It is no pleasure to me to triumph over any one; but I give thanks to the Almighty for this evidence of the people's resolution to stand or free government and the rights of humanity.

|

| Lincoln in 1864 |