|

| Cold Harbor |

|

| Confederate entrenchments at Cold Harbor |

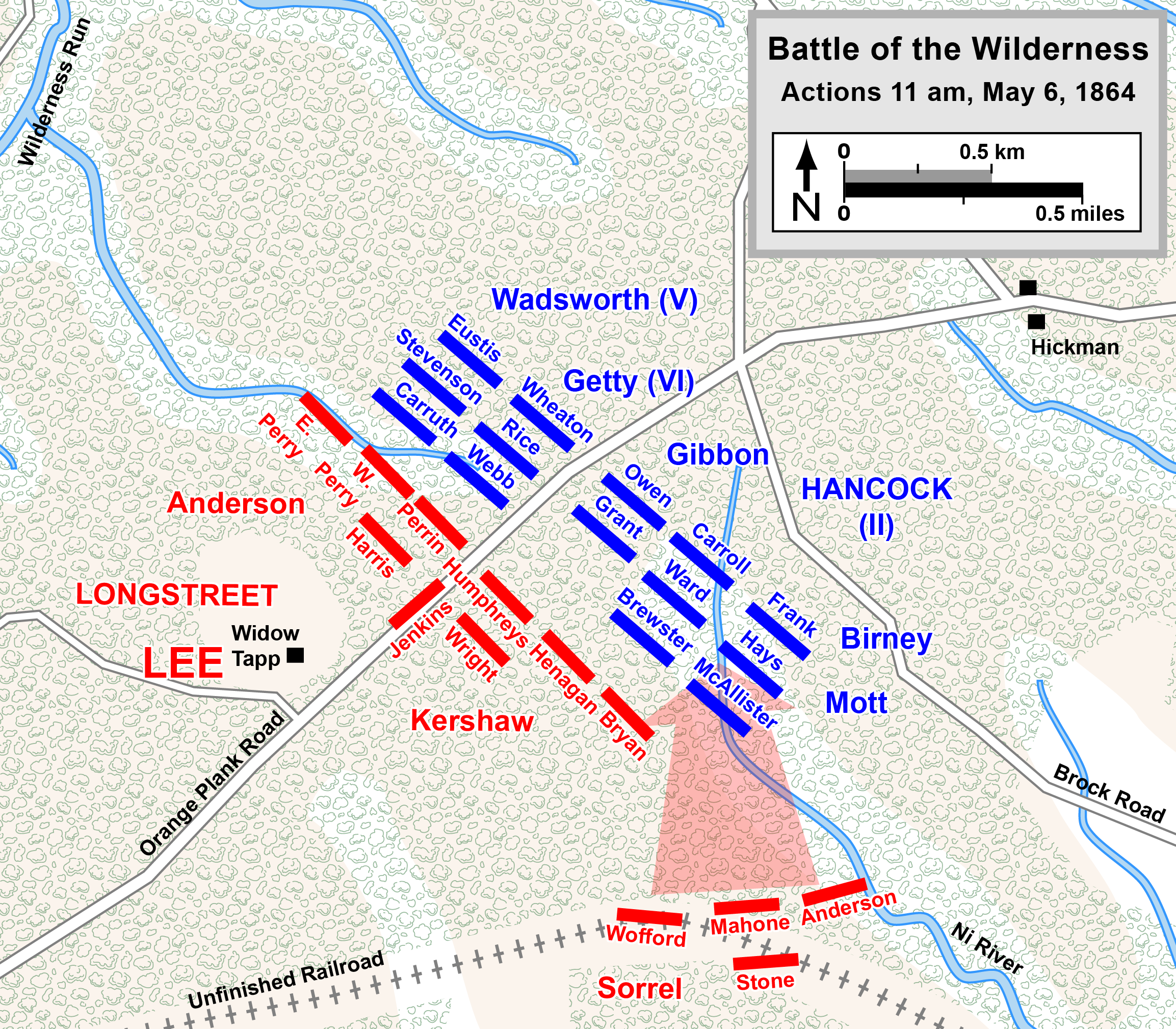

Grant, however, saw opportunities. He ordered Hancock's II corps to Cold Harbor to renew the attack the next day. In their night march, they were led down the wrong road, which delayed their arrival time. When they did reach Cold Harbor the men were exhausted, and it was decided to delay the attack until the next day, June 3rd. Confederate reinforcements also arrived along with engineers who worked to improve the entrenchments and get the best fields of fire. At the ravine where Upton had gained success a new line was established to ensure the same thing did not happen again.

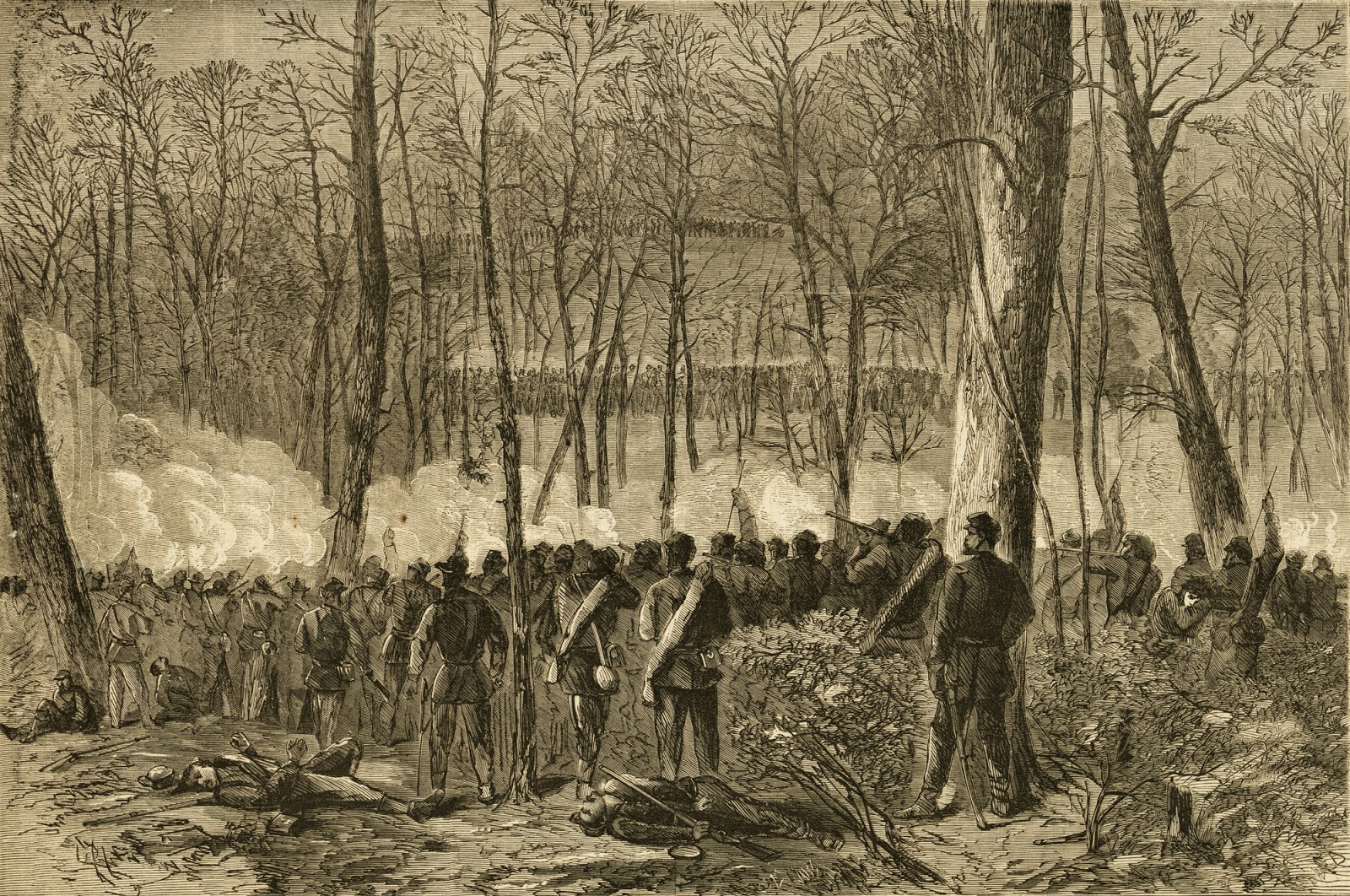

A light rain fell throughout the night, and the Union troops woke early to form for their attack. At 4:30 am, a signal round was fired, and an artillery bombardment was begun. For 10 minutes, shells were thrown into the Confederate works. Then the Yankee infantry jumped out of their works and went forward at the attack. Some Federals gained an initial success. Two of Hancock's brigades found a gap in the Confederate line, where a rebel commander had allowed his infantry to retire to a more pleasant camp. But along most of the line, the attacks met sheets of lead. One soldier wrote:

To give a description of this terrible charge is simply impossible, and few who were in the ranks ... will ever feel like attempting it. To those exposed to the full force and fury of that dreadful storm of lead and iron that met the charging column, it seemed more like a volcanic eruption than a battle, and was just about s destructive.... The men went down in rows, just as they had marched in the ranks, and so many at a time that many of the rear thought they were lying down.

The Confederates did not just fire from their trenches. They counter attacked in force, and sealed the gap that had been found in the line. Many Yankees were pinned down by the fire, and they tried to dig rifle pits with cups and bayonets. Based on some reports of a partial success, Meade ordered the attacks to be continued, but they were still not successful. Every Federal charge was beaten back with loss. At noon, Grant gave permission to Meade to call off the attack. The battle of Cold Harbor was over. The Federals had suffered tremendous casualties. Thousands of men fell in a very short period, while Lee lost only 1,500. The wounded and dead lay on the field where many of the wounded were unable to crawl away. Grant delayed agreeing on a truce for several days, and by the time one was called several days later, it was too late for any of wounded to be saved. All who had not already been carried off had died on the field.

|

| Casualties of Cold Harbor |

I have always regretted that the last assault at Cold Harbor was ever made. I might say the same thing of the assault of the 22d of May, 1863, at Vicksburg. At Cold Harbor no advantage whatever was gained to compensate for the heavy loss we sustained. Indeed, the advantages other than those of relative losses, were on the Confederate side. Before that, the Army of Northern Virginia seemed to have acquired a wholesome regard for the courage, endurance, and soldierly qualities generally of the Army of the Potomac. They no longer wanted to fight them "one Confederate to five Yanks." Indeed, they seemed to have given up any idea of gaining any advantage of their antagonist in the open field. They had come to much prefer breastworks in their front to the Army of the Potomac. This charge seemed to revive their hopes temporarily; but it was of short duration. The effect upon the Army of the Potomac was the reverse. When we reached the James River, however, all effects of the battle of Cold Harbor seemed to have disappeared.

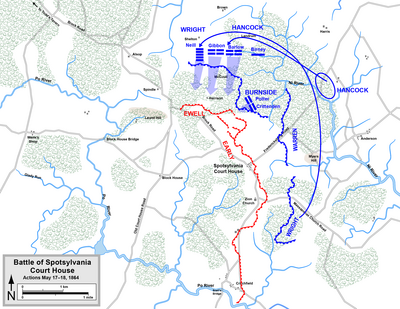

.png/450px-Battle_of_Spottsylvania_(1).png)