Tunnel Hill

150 years ago today, the Federals executed their attack on the Confederates at Chattanooga. Hooker was to continue to press on the Confederate right, Sherman on the left, and Thomas in the center. Sherman was at a positioned called Tunnel Hill. His 16,600 men were met at first by only 4,000 under Patrick Cleburne, who barely made it back to the battle in time. Cleburne's brave men were entrenched on Tunnel Hill which took its name from the railroad tunnel which cut through it. Sherman had chosen the strongest position on the Confederate line to attack. At dawn he sent two brigades forward under Brigadier General John Corse. They were stopped hard by Cleburne's men. The Confederates could throw stones down from their position and do almost as much damage as the bullets they shot. Corse's men could make no headway and were forced back. Sherman sent more lines forward, dashing them against Cleburne's line. One Federal wrote,

We had been concealed from the enemy all the forenoon by the edge of a wood; yet his constant shelling of this wood showed that he knew we were there. As the column came out upon the open ground, and in sight of the rebel batteries, their renewed and concentrated fire knocked the limbs from the trees about out heads. An awful cannonade had opened on us. ... I had heard the roaring of heavy battle before, but never such a shrieking of cannon-balls and bursting of shells as met us on that run. We could see the rebels working their guns, while in plain view other batteries galloped up, unlimbered and let loose upon us. ... In ten minutes the field was crossed, the foot of the ascent was reached, and now the Confederates poured into our faces the reserved fire of their awful musketry. It helped little that we returned it from our own rifles, hidden as the enemy were in rifle pits, behind logs, and stumps, and trees. ... Then someone cried, 'Look to the tunnel!' There, on the right, pouring through a tunnel in the mountain, and out of the railway cut, came the graycoats by hundreds, flanking us completely. ... They were through by the hundreds, and a fatal enfilading fire was cutting our line to pieces.

Sherman continued attacking for six hours, never breaking through the rebel line. When the Federals gained any foothold, Cleburne shifted his troops and launched a strong counterattack, himself at the head of his men. Charging down the hill they broke the Federal lines. By late in the afternoon, Sherman's attacks had accomplished nothing. He had lost almost 2,000 men, while Cleburne had skillfully held his position, loosing only about 200. One Confederate who visited the battlefield wrote,

They had swept their front clean of Yankies, indeed, when I went up about sundown the side of the ridge in their front was strewn with dead yankies & looked like a lot of boys had been sliding down the hill side, for when a line of the enemy would be repulsed, they would start down hill & soon the whole line would be rolling down like a ball, it was so steep a hill side there.

|

| Grant watching the battle |

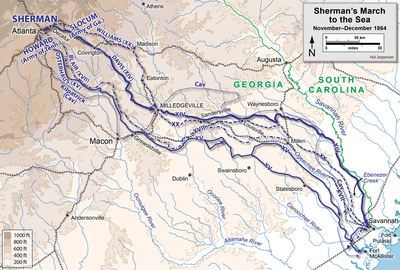

Missionary Ridge

Not all of the Confederate line had put up such a good fight as Cleburne. The odds in the center of the Confederate line were much better for the Confederates. While Cleburne had only one division to fight six, here Bragg had four to Thomas's five. In the center, Grant ordered Thomas to go forward at 3:30 pm after it was clear Sherman was making no headway. Ten minutes after the order was given, six cannon rang out, the signal for the 25,000 Federals to move forward towards the Confederate gun pits. Bragg had 112 cannon on the 400 foot ridge, and they opened at once on the advancing Northerners. The cannon balls tore into the Federal lines, but they were not halted. They broke into a run towards the ridge, with yells of "Chickamauga! Chickamauga!", remembering their defeat of a few weeks before. They rushed forward and captured the line of rifle pits. The second Confederate line in the middle of the ridge opened a heavy fire upon the intruders. At first the men were pinned down, but instead of fleeing, the men began to move slowly up the slope. They had no orders to advance, they moved of their own accord. They wanted to come to grips with the enemy rather than lay there and be shot. One Yankee wrote:

Above, the summit of the hill was one sheet of flame and smoke, and the awful explosions of artillery and musketry made the earth fairly tremble. Below, the columns of dark blue, with the old banner of beauty and of glory leading them on, were mounting up with leaning forms.... Cannon shot tore through their ranks; musket balls were rapidly and tearfully decimating them; behind them, the dead and wounded lay thick as autumn leaves.... With a wild cheer and a madder rush our men dashed forward, and for a few moments a sharp, desperate, almost hand-to-hand fight with bayonet and ball ensued. Before this resistless assault the rebel line was lifted as by a whirlwind, and borne backward, shattered, bleeding and confused.

The strong position was not taken just because of the bravery of the Federal troops, there were problems with the position itself. Although it was strong naturally, that strength made the defenders careless. The order for the first line to fall back after a few volleys had not been communicated to all the troops, so there was confusion and demoralization. The engineers had also made a bad mistake, placing the top line of rifle pits on the geographical crest rather than the military crest. On Missionary Ridge the defenders had blind spots, since they were on the actual crest. When the Federals came up the hill, not stopped by the Confederate volleys, the men broke and ran for the rear. The officers tried to stem the rout, but it was of no use. Bragg himself tried to rally them, but they ignored him. “Grey clad men rushed wildly down the hill and into the woods,” a Yankee wrote, “tossing away knapsacks, muskets and blankets as they ran. Batteries galloped back along the narrow, winding roads with reckless speed, and officers, frantic with rage, rushed from one panic-stricken group to another, shouting and cursing as they strove to check the headlong flight, but all in vain.”

37 cannon and 3000 men were captured, and Bragg himself barely made his escape. The Confederate center was completely wrecked. the Federals had suffered heavily as well. Sheridan alone, who had delivered the heaviest assault, had lost 1,346 of his 6500 men. Some regiments had over half their men killed or wounded. They halted for a time at the top of the ridge, resting on their gains. The Confederates on the left and right of the line tried to contain the breakthrough as much as possible, fighting the Federals from both directions. Cleburne's men held their ground until after sunset, and they retreated last, the unbroken rear guard of Bragg's army.

|

| Missionary Ridge |

During the course of this several day battle for Chattanooga, Bragg had lost 361 killed, 2160 wounded and 4146 captured, while Grant had 753 killed, 4722 wounded and 349 captured. But more importantly, Confederate control of Chattanooga, the gateway to the South, had been lost. Many mistakes had been made which caused Bragg to lose his very strong position. He had bad relations with many of his subordinates, causing some very talented men to have to be removed from his command so that the army could continue to function. Longstreet had been sent to East Tennessee, weakening the force. The entrenchments on Missionary Ridge had been badly positioned, and orders to the men had been confused. By this time, most of the Confederates were veterans. They knew when to stand and fight and when to run. When they thought they had no chance of success, they ran, with the exception of Cleburne's men on the right.