Troops were moving before dawn on the morning of July 21

st. Both of the armies on either side of Bull Run had similar strategies, for their left to attack their opponent's right. But that is not how it turned out. Almost all military movements are late. This is even more true when green, inexperienced troops are involved, and both of these armies were made up of troops that had never been in combat. But through the coarse of events the Union army was able to strike first. Although they were delayed on the road, because of lost orders the Confederates had not even started to move by the time they realized they were completely outflanked by the Union forces.

Evan's Brigade was the only force in position to meet the Union attack on the Confederate left. He only had two small regiments, but he used them to great effect. After meeting an attack at the Stone Brigde, he correctly guessed that the main attack would come further to the left. He also received news of the flanking movement from the signal officers of the Confederate army. He put his troops in position on a low hill. On the way were the brigades of Bee and Bartlow as reinforcements.

When Evans saw the Union advance, he opened fire and charged. The attack held back the Union troops just long enough for Bee's Brigade to arrive, tired and panting from having ran several miles to reach the threatened point in time. Major Wheat of the 1st Louisiana was wounded in the attack. He was commander of Wheat's Louisiana Tigers, a fearsome battalion recruited from the docks of New Orleans. As he lead his bowie knife welding men forward, he received a bullet through his lung. When the doctor told him that there was no case upon record where a man with that kind of wound had survived, he replied, "Well then, I will put my case upon record." He did, and went on to continue to fight in the Confederate armies.

With the arrival of Bee and Bartlow's Brigades to reinforce Evans, the Confederate left was temporarily stabilized. But they were still greatly outnumbered, and under a heavy fire. They charged in an attempt to break the Union line, but after heavy fighting they were push back after suffering many casualties. They streamed the the rear being followed by the exalting Union forces. The Union pursuers halted at the base of Henry Hill to stabilize their line.

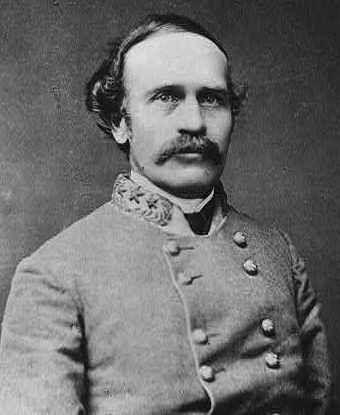

At around noon the Federal line again advanced, moving up the Confederate line. But by this time Gen. Thomas Jackson's brigade had arrived. He ordered his men to lie down behind the crest of the hill. As the other Confederate brigades began to fall back under the enemy's pressure, Bee rode up to Jackson and said, "General, they are beating us back." Jackson replied, "Sir, we'll give them the bayonet." Bee, riding back and placing himself at the head of one of his regiments that still maintained some of their order, shouted, "There is Jackson standing like a stone wall. Let us determine to die here, and we will conquer. Rally behind the Virginians. Follow Me!" He soon fell dead, shot as he was leading his troops toward the enemy. From them on Jackson and the brigade that he commanded would be known as “Stonewall.”

Jackson was able to hold firm on Henry Hill. Beauregard arrived to direct the situation on the spot, while Johnston worked to bring reinforcements to the left as fast as possible. Fighting continued for three hours on Henry Hill. Under heavy fire, there were multiple charges back and forth across the field. A charge of the Stonewall Brigade captured Rickett’s and Griffin’s batteries. JEB Stuart’s cavalry broke an enemy line with a charge. There was much confusion between the troops. Many Confederates wore blue, and the Stars and Bars hanging limp on the flagstaff, looked much like the Stars and Stripes.

Finally between 4:00 and 4:30 the Union line began a full out retreat. The Confedeate line on Henry Hill had held firm, and with the arrival of fresh troops from Early’s Brigade, and Kirby Smith’s Brigade, which came right off the trains from the Shenandoah Valley, they were able to push forward. The Northerners fled with cries of “The enemy is upon us! We shall all be taken!” McDowell made the mistake of waiting to long to order a retreat. If he had not held on until the last minute, he could have made an orderly retreat. But instead there was a rout all the way to Washington. One man described it thus:

“Then a scene of confusion ensued which beggars description. Cavalry horses with out riders, artillery horses disengaged from the guns with traces flying, wrecked baggage-wagons, and pieces of artillery drawn by six horses without drivers, flying at their utmost speed and whacking against other vehicles.... The rush produced more noise than a hurricane at sea.”

The Confederates did not pursue far. They were worn out, and the next day rain turned the road into mud. Had this not occurred, they may have been able to quickly end the war by capturing Washington and forcing the North to let them go. But instead, not much happened for the next few months. Both sides recognized that the war would not be as quick as they thought. They began to see that it would be long and bloody, and well trained, professional soldiers would be needed.

Although he was not the Confederate supreme commander, Beauregard received the praise for the victory at Bull Run. Although it was Johnston who had the responsibility and really ran the battle, Beauregard was a much more romantic figure. The stories of him riding along the lines and leading charges against the North were much more appealing than Johnston sending orders and bringing up reinforcements.

So why did this battle turn out the way it did? The Confederates were victorious not because of wise strategic decisions made by the generals. Their plan had failed miserably, but they fought hard and stumbled upon strong positions such as Henry Hill. The Union were unsuccessful because they were tired from their long march, and did not have the superiority they had hoped for because Johnston had arrived to reinforce Beauregard. McDowell did not really do that bad of a job. But he relied on green troops and green officers who did not know how a battle should be fought. Sherman, who later became one of the leading Northern generals, said this, “Bull Run Battle was lost by us not from want of combination, strategy or tactics, but because our army was green as grass.” “[It] was one of the best planned battles of the war, but one of the worst-fought. Both armies were fairly defeated, and whichever stood fast the other would have run.”