|

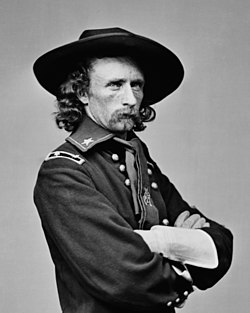

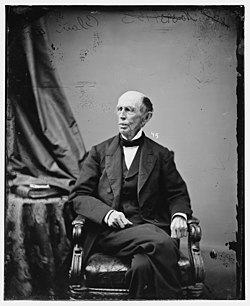

| Francis Blair |

As the bloody Civil War raged on into 1865,

nearly everyone on both sides longed for peace. There were some who

believed that peace could be reached through negotiation, without one

side winning a complete victory. One of these was Fancis Preston

Blair, a northern politician and journalist who had close personal

relations with many in the Confederate government. With Lincoln's

permission, he traveled to Richmond in January, 1865 to propose a

peace conference. Jefferson Davis was interested, if only to harden

the Confederacy's resolve by showing that a negotiated peace was not

possible. However, a major issue soon surface. Davis wrote to Lincoln

that he was ready to receive a c omission “with a view to secure

peace to the two countries.” Lincoln told Blair that he would

receive any agent that Jefferson Davis “may informally send to me

with a view to securing peace to the people of our one common

country.” For Davis, the Confederacy's independence was

non-negotiable, but Lincoln would only consider a proposal that

resulted in a unified country.

|

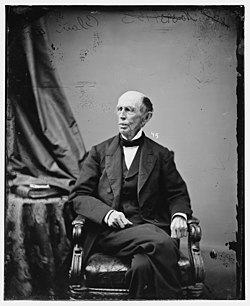

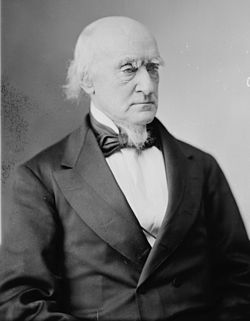

| Alexander Stephens |

Blair, with help from Grant, was able to smooth

over this difference, and a Peace Conference met. It was held on

February 3rd, 150 years today, on the Union steamer River Queen off Fort Monroe, Virginia. Representing the Union was

Abraham Lincoln and Secretary of State William Seward. From the

Confederacy was vice-president Andrew Stephens, who had broken with

Davis and pushed for a speedy peace, Senator Robert Hunter of

Virginia and John Campbell, former US Supreme Court Justice and

Confederate Assistant Secretary of War.

|

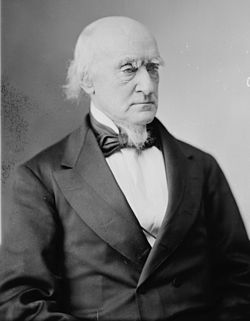

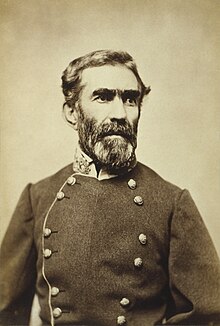

| John Campbell |

Stephens opened the meeting by discussing the

French invasion of Mexico. One of Blair's suggestions was the country

could be reunified if the Civil War was halted with an armistice, and

north and south united in sending an expedition to repel Napoleon

III's invasion of Mexico. Lincoln, however, quickly cut him off, and

turned to the question of sovereignty. Would there be one country or

two? It was instantly apparent that the conference was useless. As

John Campbell wrote, “We learned in five minutes that [Blair's]

assurances to Mr. Davis were a delusion, and that union was the

condition of peace.” Neither side would yield upon this crucial

point.

|

| Seward |

The conference continued some time longer, with

a discussion of slavery, a proposal from Lincoln to compensate to the

south for their slaves, and whether if the southern states

immediately surrendered they could reject the 13th

Amendment. The one result of the convention was that Lincoln promised

to recommend that Grant reopen prisoner exchanges.

|

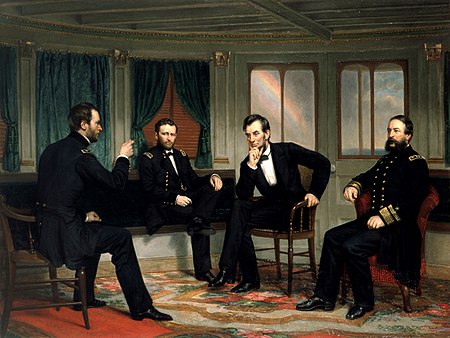

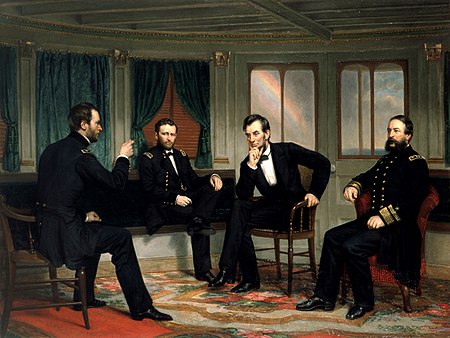

| The River Queen |

The main product of the meeting was propaganda

material for both sides. Jefferson Davis could tell the South that he

had tried his best to arrange a peace with the North, but they only

terms they offered was absolute surrender. The Confederacy's only

hope was to fight to the end. Abraham Lincoln could say that the

south still remained unwilling to compromise on their independence,

and the Yankee troops needed to fight the war to the finishing,

reaping the complete fruits of victory with the abolition of slavery.

|

| Lincoln on the River Queen several weeks later |

.jpg/250px-John_Newton_(ACW).jpg)