The Battle of Cherbourg was fought off of France on June 19, 1864, between the United States warship Kearsarge and the Confederate raider Alabama. For months the Alabama had sailed the oceans of the world, wreaking havoc in the Union shipping. But when she came into Cherbourg for repairs she was caught by the Kearsarge. Raphael Semmes, the Confederate captain, had the option to remain holed up in port for probably the rest of the war, or to take a chance and take on the Union ship. He chose the bolder course, and so went out to battle. Semmes wrote of the battle:

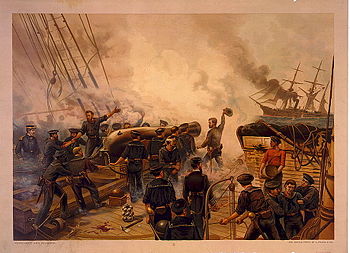

We were three quarters of an hour in running out to the Kearsarge, during which time we had gotten our people to quarters, cast loose the battery, and made all the other necessary preparations for battle. The yards had been previously slung in chains, stoppers prepared for the rigging, and preventer braces rove. It only remained to open the magazine and shell-rooms, sand down the decks, and fill the requisite number of tubs with water. The crew had been particularly neat in their dress on that morning, and the officers were all in the uniforms appropriate to their rank. As we were approaching the enemy's ship, I caused to be sent aft, within convenient reach of my voice, and mounting a gun-carriage, delivered the following brief address. I had not spoken to them in this formal way since I had addressed them on the memorable occasion of commissioning the ship.

“Officers And Seamen Of The Alabama!—You have, at length, another opportunity of meeting the enemy—the first that has been presented to you, since you sank the Hatteras! In the meantime, you have been all over the world, and it is not too much to say, that you have destroyed, and driven for protection under neutral flags, one half of the enemy's commerce, which, at the beginning of the war, covered every sea. This is an achievement of which you may well be proud; and a grateful country will not be unmindful of it. The name of your ship has become a household word wherever civilization extends. Shall that name be tarnished by defeat? The thing is impossible! Remember that you are in the English Channel, the theatre of so much of the naval glory of our race, and that the eyes of all Europe are at this moment, upon you. The flag that floats over you is that of a young Republic, who bids defiance to her enemies, whenever, and wherever found. Show the world that you know how to uphold it! Go to your quarters.”

… My official report of the engagement, addressed to Flag-Officer Barron, in Paris, will describe what now took place. It was written at Southampton, England, two days after the battle.

When within about a mile and a quarter of the enemy, he suddenly wheeled, and, bringing his head in shore, presented his starboard battery to me. By this time, we were distant about one mile from each other, when I opened on him with solid shot, to which he replied in a few minutes, and the action became active on both sides. The enemy now pressed his ship under a full head of steam, and to prevent our passing each other too speedily, and to keep our respective broadsides bearing, it became necessary to light in a circle; the two ships steaming around a common centre, and preserving a distance from each other of from three quarters to half a mile. When we got within good shell range, we opened upon him with shell. Some ten or fifteen minutes after the commencement of the action, our spanker-gaff was shot away, and our ensign came down by the run. This was immediately replaced by another at the mizzen-mastliead. The firing now became very hot, and the enemy's shot, and shell soon began to tell upon our hull, knocking down, killing, and disabling a number of men, at the same time, in different parts of the ship. Perceiving that our shell, though apparently exploding against the enemy's sides, were doing him but little damage, I returned to solid-shot firing, and from this time onward alternated with shot, and shell.

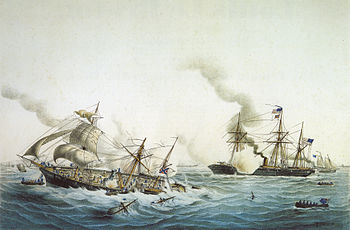

After the lapse of about one hour and ten minutes, our ship was ascertained to be in a sinking condition, the enemy's shell having 'exploded in our side, and between decks, opening large apertures through which the water rushed with great rapidity. For some few minutes I had hopes of being able to reach the French coast, for which purpose I gave the ship all steam, and set such of the fore-and-aft sails as were available. The ship filled so rapidly, however, that before we had made much progress, the fires were extinguished in the furnaces, and we were evidently on the point of sinking. I now hauled down my colors, to prevent the further destruction of life, and dispatched a boat to inform the enemy of our condition. Although we were now but 400 yards from each other, the enemy fired upon me five times after my colors had been struck. It is charitable to suppose that a ship of war of a Christian nation could not have done this, intentionally. 'We now directed all our exertions toward saving the wounded, and such of the boys of the ship as were unable to swim. These were dispatched in my quarter-boats, the only boats remaining to me; the waist-boats having been torn to pieces. Some twenty minutes after my furnace-fires had been extinguished, and when the ship was on the point of settling, every man, in obedience to a previous order which had been given the crew, jumped overboard, and endeavored to save himself. There was no appearance of any boat coming to me from the enemy, until after my ship went down. Fortunately, however, the steamyacht Deerhound, owned by a gentleman of Lancashire, England —Mr. John Lancaster—who was himself on board, steamed up in the midst of my drowning men, and rescued a number of both officers and men from the water. I was fortunate enough myself thus to escape to the shelter of the neutral flag, together with about forty others, all told. About this time, the Kearsarge sent one, and then, tardily, another boat. … My officers and men behaved steadily and gallantly, and though they have lost their ship, they have not lost honor. … The enemy was heavier than myself, both in ship, battery, and crew; but I did not know until the action was over, that she was also iron-clad. Our total loss in killed and wounded, is 30, to wit: 9 killed, and 21 wounded.

0 comments:

Post a Comment