Friday, August 31, 2012

Lee Pursues Pope

After defeating Pope in the Battle of 2nd Manassas, Lee mounted a pursuit, hoping to destroy Pope's entire army and achieve a victory like Kirby Smith's in Kentucky. Pope and his subordinates believed that it was time to retreat to the Washington defenses, but Henry Halleck in Washington sent him a message ordering him to advance on Lee. Lincoln and Halleck didn't want Pope to fall back because he had simply lost his nerve. Pope, however, was still in great danger from Lee. Jackson had been sent out again on another great flanking march, moving around Pope's position at Centerville, VA, while Longstreet remained in position at Manassas. As Pope's men slept on August 31st, Jackson's men were nearby, just three miles to the northeast, on the verge of getting around Pope's flank.

Labels:

campaign,

John Pope,

Robert E. Lee,

Virginia

Thursday, August 30, 2012

Battle of Richmond

|

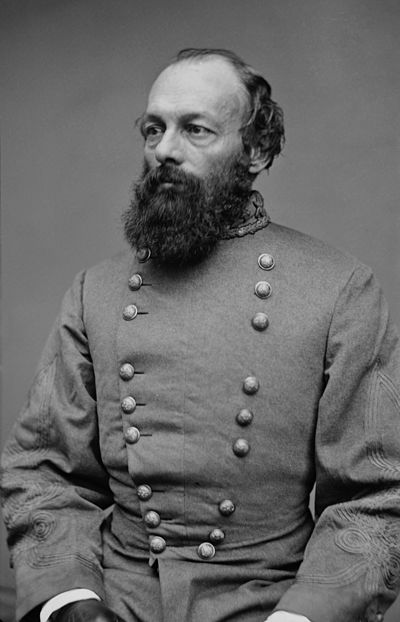

| Kirby Smith |

|

| Manson |

Although the withdrawal was in bad order, Manson was able to rally his men around 11 am. However, Kirby Smith ordered Churchill to attack on the right and he was successful again, in thirty minutes shattering Manson's new line and sending the Yankees retreating back to the town of Richmond.

|

| Nelson |

The chief Federal commander, William “Bull” Nelson, arrived on the field and put whatever troops he could in a cemetery just outside of Richmond. Smith again attacked the right flank and collapsed the Union line, driving the defeated Federals through the streets of Richmond. Kirby Smith had sent the cavalry under Colonel John Scott to cut the Federal retreat, and these troops now struck them on the march just after dark, two miles north of Richmond. The tired Federals, thrice defeated, were no match for the southern horsemen. They were captured in droves, and few Federals made their escape.

|

| Cleburne |

Of about 7,000 Yankees engaged, 200 were killed, 850 wounded and the rest were captured, except for 500 men, including Nelson, who were able to make their escape. The Confederates lost 80 killed, 370 wounded and only 1 missing. This was the most complete battlefield victory achieved during the war. Throughout the war the goal was always not only to defeat and drive back the enemy, but to capture so many men that the opposing army would cease to exist, as Hannibal had famously achieved at Cannae. This was the closest any commander came to achieving that Cannae. The Federal force ceased to exist, and the way to invasion was opened.

Labels:

battle,

campaign,

Kentucky,

Kirby Smith,

Patrick Cleburne

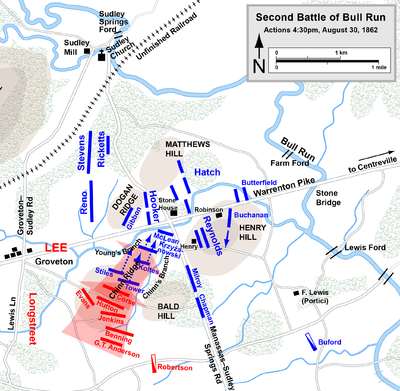

Battle of 2nd Manassas – Day 3

|

| The Deep Cut of the Unfinished Railroad, Jackson's position |

Throughout the morning the battlefield was calm, as the Federal troops were not prepared to attack. The Confederates began to think that there would be no battle that day, but after noon Pope's troops moved forward. It took a long time to maneuver 10,000 men into the proper position. They faced a difficult assignment. They had to march across several hundred yards of open fields, and then attack the Confederates in the unfinished railroad. Although they took heavy casualties in the advance, their attack achieved some success. Charging across the field they drove back the Confederate infantry holding the line. Troops including the Stonewall Brigade were rushed forward to stem the breech, and the fighting was very fierce around the unfinished railroad. The Confederates in several units fired all their ammunition, but they still clung to their line, throwing down stones on the Federals rather than give up their position. A soldier of the Stonewall Brigade wrote:

It was one continuous roar from right to left. My brigade was in a small cut, with a field in front sloping down about four hundred yards to a piece of wood. The enemy would form in the woods and come up the slope in three lines as regular as if on drill, and we would pour volley after volley into them as they came; but they would still advance until within a few yards of us, when they would break and fall back to the woods, where they would rally and come again.Although they were holding for the moment, their position was far from safe. Lee sent a message to Longstreet ordering him to send a division to reinforce Jackson. Instead, Longstreet ordered that the artillery be opened. Firing into the Federal flank, they soon decimated their formations and sent them running to the rear. They day was saved. Longstreet ordered his men forward, and with a rebel yell they charged, their left guarded by Jackson's tired men. Driving through the Federal troops, they encountered stiffer resistance from McLean's brigade on Chinn Ridge. McLean had only 1200 men, but he held out against two assaults. However, on the third charge he was overpowered and his men were forced to fall back.

Although they had been forced back, Pope had been given more time to organize a defense. The Confederates continued their assaults, and were able to drive back the Federals from their positions, although at a large cost of blood and time. Lee ordered the reserve, Richard Anderson's division, in an attempt to finish off the battle. Anderson's attack created a gap in the Federal battle line, but he did not exploit it, possibly because of the coming darkness. During the night Pope ordered the Federals to fall back. Unlike First Manassas, they retreated in an orderly fashion.

Lee's army had failed to achieve a complete destruction of Pope's army, but he had still won a great victory. The Confederates had defeated Pope decisively. He had been soundly out generaled by Lee. He blamed the failure on Fitz-John Porter, who was courtmarshaled and found guilty of disobedience. However, fifteen years later he was exonerated of all charges, and it was acknowledged that by his reluctance to attack he prevented an even worse defeat. Pope himself should have borne the blame for his defeat. He lost 1,716 killed, 8,215 wounded and 3,893 missing. Lee had lost 1,305 killed and 7,048 wounded.

Labels:

battle,

James Longstreet,

John Pope,

Manassas,

Robert E. Lee,

Stonewall Jackson,

Virginia

Wednesday, August 29, 2012

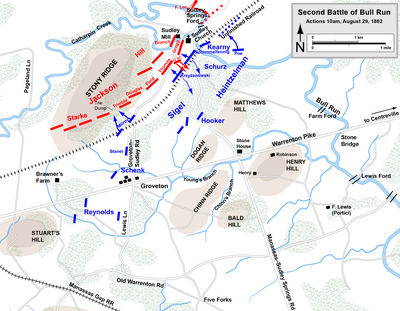

Battle of 2nd Manassas – Day 2

|

| Pope |

Sigel launched four attacks on Jackson throughout the day, but they were not followed up with the forces necessary to break through. Jackson's men fought hard in defense of the railroad cut. When they were pushed back, they responded by charging in counterattacks which drove back the Federals. An attack by Grover's brigade struck a gap in the Confederate line between Thomas and Gregg. In the confused wooded section along A. P. Hill's section of the line, Grover at first gained some success, but Pender's brigade moved forward and threw him back. One Confederate soldier vividly remembered the fighting:

[W]e remained at the railroad, and, after a short halt, the announcement 'Here they come!' was heard. A line of battle marched out of the far end of the east wood into the field, halted, dressed the line, and moved forward. They were allowed to come within about one hundred yards of us, when we opened fire. We could see them stagger, halt, stand a short time, break, and run. At this this time another line made its appearance, coming from the same point. It came a little nearer. They too broke and ran. Still another line came nearer, broke and ran. The whole field seemed to be full of Yankees and some of them advanced nearly to the railroad. We went over the bank at them, the remainder of the brigade following our example.Longstreet's men finally arrived and came into position at around 1 PM. His corps was placed almost at right angles to Jackson's line, the two lines meeting at Brawner's Farm. Lee wished to make an attack on the Federals, but Longstreet convinced him to wait until the next day. The bloody day finally came to an end, with Lee's army reunited, and unbroken by Federal attacks.

Labels:

battle,

James Longstreet,

John Pope,

Manassas,

Robert E. Lee,

Stonewall Jackson,

Virginia

Tuesday, August 28, 2012

Battle of 2nd Manassas – Brawner's Farm

On the morning of August 28th, Jackson was concentrating his scattered forces northward around the old battlefield of Bull Run, where the Confederates had won a grand victory in the first battle of the war. Pope, who by now knew of Jackson's presence in his rear, was advancing north towards Jackson at Manassas, but he had neglected to scout for the position of the rest of the Confederate army. Lee had moved with Longstreet's Corps two days before, and they were marching to join Jackson, along the same route, a few days behind. On this very day Longstreet captured Thoroughfare Gap, driving off the Federals and clearing the way for his union with Jackson. Jackson had to hold out against Pope until the army was reunited when Longstreet arrived. However, this did not stop his usual aggressiveness. He wanted to strike a blow at Pope, and lure him to assault him, and so formed his men in an old railroad cut, and waited for an opportunity.

Around sunset, a Union column was sighted moving across the Confederate front. A Confederate staff officer vividly remembered the occurrence:

The divisions of Ewell and Taliaferro charged toward the Federals, which proved to be the division of Rufus King, commanded in his absence by Abner Doubleday, one of the officers at Fort Sumter. The unit the Confederates hit first was the Iron Brigade under John B. Gibbon, one of the few Western Units in the army. It was also known as the Black Hat Brigade because of their distinctive headgear. They did not take to the heels, but instead stood and fought hard against the superior numbers facing them. Major Rufus Dawes of the 6th Wisconsin remembered:

Pope was now alerted to Jackson's exact position, and doubtless a battle would follow the next day. Jackson however, had reason to be confident of his position. He occupied a strong defensive position, and Longstreet was marching fast to join him.

Jackson rode out to examine the approaching foe, trotting backwards and forwards along the line of their handsome parade marching by, and in easy musket range of their skirmish, but they did not seem to think that a single horsemen was worthy of their attention-how little they thought that this single, plainly dressed horseman was the great Stonewall himself, who was then deliberating in his own mind the question of hurling his eager troops upon their devoted heads. ... Sometimes he would halt, then trot on briskly, halt again, wheel his horse and bass again along the front of the march column, or rather along its flank. About a quarter of a mile off, troops were now opposite us. All felt sure Jackson could never resist that temptation, and that the order to attack would come soon, even if Longstreet was beyond the mountain. Presently General Jackson pulled up suddenly, wheeled and galloped toward us. ... [T]ouching his hat in military salute, said in as soft a voice as if he had been talking to a friend in ordinary conversation, 'Bring up your men gentlemen.' Every officer whirled around and scurried back to the woods at full gallop. The men had been watching their officers with much interest and when they wheeled and dashed toward them they knew what it meant, and from the woods arose a hoarse roar like that from cages of wild animals at the scent of blood.

The fighting continued fiercely for two and a half hours around Brawner's Farm. Both sides fought hard and many men fell. Confederate General Taliaferro remembered:Our men on the left loaded and fired with the energy of madmen, and the 6th worked with equal desperation. This stopped the rush of the enemy and they halted and fired upon us their deadly musketry. During a few awful moments, I could see by the lurid light of the powder flashes, the whole of both lines. I saw a rebel mounted officer shot from his horse at the very front of the battle line. It was evident that were were being overpowered and that our men were giving ground. The two crowds, they could hardly be called lines, were were within ... fifty yards of each other pouring musketry into each other as fast as men could load and shoot. Two of General Doubleday's regiments ... now came suddenly into the gap on the left of our regiment, and they fired a crashing volley. Hurrah! They have come at the very nick of time. The low ground saved our regiment, as the enemy overshot us in the darkness.

Dawes

The fighting finally wound to a close around 9:00 pm. Neither side was able to drive the other from the field. The Federals had held their own, and Jackson had been unable to crush them. Casualties had been high on both sides. Especially important to Jackson was the loss of two of his division commanders, Taliaferro and Ewell were both wounded. Many units were now mere shadows of their former selves, the famed Stonewall Brigade for example, left 340 on the field of the 800 men with which they entered the battle.A farm-house, an orchard, a few stacks of hay, and a rotten "worm" fence were the only cover afforded to the opposing lines of infantry; it was a stand-up combat, dogged and unflinching, in a field almost bare. There were no wounds from spent balls; the confronting lines looked into each other's faces at deadly range, less than one hundred yards apart, and they stood as immovable as the painted heroes in a battle-piece. There was cover of woods not very far in rear of the lines on both sides, and brave men--- with that instinct of self-preservation which is exhibited in the veteran soldier, who seizes every advantage of ground or obstacle---might have been justified in slowly seeking this shelter from the iron hail that smote them; but out in the sunlight, in the dying daylight, and under the stars, they stood, and although they could not advance, they would not retire. There was some discipline in this, but there was much more of true valor. In this fight there was no maneuvering, and very little tactics---it was a question of endurance, and both endured.

Taliaferro

Pope was now alerted to Jackson's exact position, and doubtless a battle would follow the next day. Jackson however, had reason to be confident of his position. He occupied a strong defensive position, and Longstreet was marching fast to join him.

|

| Brawner Farm. Source. |

Labels:

battle,

Iron Brigade,

John Gibbon,

John Pope,

Manassas,

Richard Ewell,

Stonewall Jackson,

Virginia

Monday, August 27, 2012

Jackson's Great Flanking March

Lee and his generals, disappointed at the failure to destroy Pope between the Rapidan and Rappohannock Rivers, turned to other plans. On August 23rd, J.E.B. Stuart rode around Pope's flank in a cavalry intelligence raid, and on the way he raided Pope's headquarters in retribution for the Union cavalry raid which captured Stuart's headquarters the day before. He captured 300 prisoners, the army dispatch book, and Pope's hat and uniform. Stuart, having lost his hat to the Yankees, proposed an exchange of prisoners, but when he was refused he sent the hat and coat to Richmond to be displayed.

|

| John Pope |

More importantly, the captured dispatches told Lee that he had to move quickly, because McClellan's army was on its way to join Pope. He had to strike before these reinforcements arrived. He also did not want to try a head on attack across the river, so instead he planned to cross upstream. Stonewall Jackson would move around Pope's right with his entire corps and cut communications with Washington, while Longstreet kept him occupied on the front. Then the two corps would reunited, crushing Pope between. It was a daring plan, as if Pope knew what was happening he could easily turn and destroy one part of the divided army. Lee knew he was violating the rules of warfare, but he had no other choice if he was going to make an offensive effort to destroy Pope.

On August 25th, Jackson set out on his dangerous march. He moved carefully, as one false step could expose the plan and give up the army to destruction. His “foot cavalry,” as they were called, marched hard and fast without luggage, the orders, "Close up men, close up," traveling up and down the line. When the troops saw Jackson, they refrained from the usual cheers to prevent disclosing their position, and instead tossed their hats high in the air. "Who could not conquer," Jackson said, "with such troops as these?

|

| Thoroughfare Gap via Civil War Trust |

The corps camped at night having made good time, and resumed their marching the next day. They found Thoroughfare Gap left unguarded, and continued to push on towards the railroad supply line. Jackson's tired men reached Bristoe Station in the afternoon, at the time the supply trains were coming through. They made efforts to stop the trains, but the first one got through, carrying word of Confederates on the railroad. The next one however was derailed, and it was found that it was named the President, and a Confederate bullet had gone right through a picture of Lincoln on the side. Another train was wrecked as well, but the fourth train however saw the wreck and was able to reverse the train to prevent its capture. Word of Jackson's movement was now traveling both North and South of Bristoe Station.

|

| The train the rebels derailed |

Confederate forces also pushed to Manassas Station, where they found a huge depot of Union supplies. They captured tons of stores, and two compete batteries. "A scene around the storehouses was not witnessed, but cannot be described" a hungry rebel later wrote:

Only those who participated can ever appreciate it. Remember, that many of those men were hurried off on the march ... with nothing to eat ... Now here are vast storehouses filled with everything to eat, and sutler's stores filled with all the delicacies, potted ham, lobster, tongue, candy, cakes, nuts, oranges, lemons, pickles, catsup, mustard, etc. It makes an old soldier's mouth water now to think of the good things captured there. A guard was placed over everything in the early part of the day. .. A package or two of each article was given to each company. ... Gen. Jackson's idea was that they could care for the stores until Gen. Lee came up, and turn the remainder over to him, hence he placed a guard over them. The enemy began to make such demonstrations that he decided he could not hold the place, therefore the houses were thrown open, and every man was told to help himself. Our kettle of soup was left to take care of itself. Men who were starving a few hours before, and did not know when they would get another mouthful, were told to help themselves. ... It was hard to decide to take, some filled their haversacks with cakes, some with candy, others oranges, lemons, canned goods, etc. I know one who took nothing but French mustard, filled his haversack and was so greedy that he put one more bottle in his pocket. This was his four day's rations, and it turned out to be the best thing taken, because he traded it for meat and bread ..."

Thursday, August 23, 2012

Lincoln on Freeing the Slaes

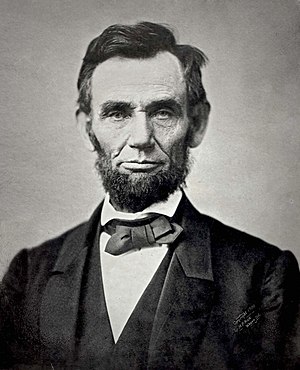

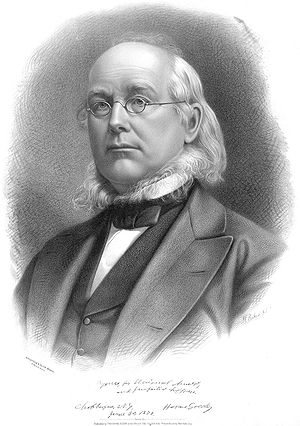

Around this time, 150 years ago, Abraham Lincoln sent a letter to Horace Greeley, who had much influence through his paper, the New York Tribune, explaining his reasoning as to freeing the slaves. Greeley had published on August 19th an open letter to Lincoln in his paper called "A Prayer of Twenty Millions." He was urging Lincoln to make more efforts to free the slave, including enforcing the Confiscation Act, which allowed the confiscation of any property of the rebels including slaves.

Executive Mansion,

Washington, August 22, 1862.

Hon. Horace Greeley:

Dear Sir.

I have just read yours of the 19th. addressed to myself through the New-York Tribune. If there be in it any statements, or assumptions of fact, which I may know to be erroneous, I do not, now and here, controvert them. If there be in it any inferences which I may believe to be falsely drawn, I do not now and here, argue against them. If there be perceptable in it an impatient and dictatorial tone, I waive it in deference to an old friend, whose heart I have always supposed to be right.

As to the policy I "seem to be pursuing" as you say, I have not meant to leave any one in doubt.

I would save the Union. I would save it the shortest way under the Constitution. The sooner the national authority can be restored; the nearer the Union will be "the Union as it was." If there be those who would not save the Union, unless they could at the same time save slavery, I do not agree with them. If there be those who would not save the Union unless they could at the same time destroy slavery, I do not agree with them. My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that. What I do about slavery, and the colored race, I do because I believe it helps to save the Union; and what I forbear, I forbear because I do not believe it would help to save the Union. I shall do less whenever I shall believe what I am doing hurts the cause, and I shall do more whenever I shall believe doing more will help the cause. I shall try to correct errors when shown to be errors; and I shall adopt new views so fast as they shall appear to be true views.

I have here stated my purpose according to my view of official duty; and I intend no modification of my oft-expressed personal wish that all men every where could be free.

Yours,

A. Lincoln.

Lincoln's letter was not all it seemed to be. For even as he wrote this letter he was considering an emancipation proclamation to aid in the restoration of the Union. With this letter he was skillfully laying the ground work for public opinion to support him when the time came.

|

| Lincoln |

Washington, August 22, 1862.

Hon. Horace Greeley:

Dear Sir.

I have just read yours of the 19th. addressed to myself through the New-York Tribune. If there be in it any statements, or assumptions of fact, which I may know to be erroneous, I do not, now and here, controvert them. If there be in it any inferences which I may believe to be falsely drawn, I do not now and here, argue against them. If there be perceptable in it an impatient and dictatorial tone, I waive it in deference to an old friend, whose heart I have always supposed to be right.

As to the policy I "seem to be pursuing" as you say, I have not meant to leave any one in doubt.

I would save the Union. I would save it the shortest way under the Constitution. The sooner the national authority can be restored; the nearer the Union will be "the Union as it was." If there be those who would not save the Union, unless they could at the same time save slavery, I do not agree with them. If there be those who would not save the Union unless they could at the same time destroy slavery, I do not agree with them. My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that. What I do about slavery, and the colored race, I do because I believe it helps to save the Union; and what I forbear, I forbear because I do not believe it would help to save the Union. I shall do less whenever I shall believe what I am doing hurts the cause, and I shall do more whenever I shall believe doing more will help the cause. I shall try to correct errors when shown to be errors; and I shall adopt new views so fast as they shall appear to be true views.

I have here stated my purpose according to my view of official duty; and I intend no modification of my oft-expressed personal wish that all men every where could be free.

Yours,

A. Lincoln.

Lincoln's letter was not all it seemed to be. For even as he wrote this letter he was considering an emancipation proclamation to aid in the restoration of the Union. With this letter he was skillfully laying the ground work for public opinion to support him when the time came.

|

| Greeley |

Labels:

Abraham Lincoln,

emancipation,

Horace Greeley,

politics,

slavery

Monday, August 20, 2012

Lee Moves Against Pope

This post is a few days behind our normal schedule, our apologies for the delay.

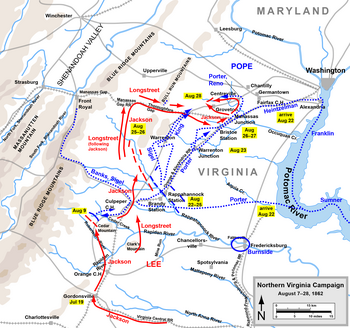

While Jackson was facing Pope north of Richmond, Lee was still facing the army of McClellan along the James River. However, 150 years ago today, Lee decided to shift his entire army to face Pope. He had guessed the Federal intentional correctly, that McClellan's forces were being shifted from the Peninsula to reinforce Pope. McClellan had protested this movement strongly. He thought that the government in Washington was abandoning a strong position. However, he had fallen out of favor since his defeat in the Seven Days campaign, and the movement would continue even over his objections. >

When Lee reunited his army in front of Pope, he called a council of war to decide on the plan of attack. Looking at a map, it was seen that Pope had gotten himself in a bad position. His men were in the peninsula formed by the Rapidan and Rappahannock rivers, and if Lee could suprise him, he might be able to destroy him by driving him against the rivers. The plan was to send Stuart's cavalry to destroy the bridges over the rivers, cutting off Pope's escape route and then quickly cross with the infantry and move in to destroy him. >

However, it did not work out quite as the Confederates planned. Instead of Stuart launching his raid in secrecy, he himself was raided. Early on the morning of August 18th Stuart was awoken by pickets announcing that cavalry were riding towards his headquarters. Fitz Lee's rebel troopers were expected to arrive from the same direction, but when Stuart rode out to check them out, he realized they were Federals. The Yankee cavalry opened fire, and Stuart wheeled his horse around and galloped off. Jumping a fence he was able to ride to safety, but the Federals were able to capture his headquarters, securing his flamboyant hat and cape, and, more importantly, dispatches from Lee detailing the plan to cut of Pope's retreat. With this information, which corroborated reports from other spys, Pope soon ordered a retreat, and was able to cross the rivers before Lee had a chance to strike.

|

| Northern Virginia Campaign |

While Jackson was facing Pope north of Richmond, Lee was still facing the army of McClellan along the James River. However, 150 years ago today, Lee decided to shift his entire army to face Pope. He had guessed the Federal intentional correctly, that McClellan's forces were being shifted from the Peninsula to reinforce Pope. McClellan had protested this movement strongly. He thought that the government in Washington was abandoning a strong position. However, he had fallen out of favor since his defeat in the Seven Days campaign, and the movement would continue even over his objections. >

When Lee reunited his army in front of Pope, he called a council of war to decide on the plan of attack. Looking at a map, it was seen that Pope had gotten himself in a bad position. His men were in the peninsula formed by the Rapidan and Rappahannock rivers, and if Lee could suprise him, he might be able to destroy him by driving him against the rivers. The plan was to send Stuart's cavalry to destroy the bridges over the rivers, cutting off Pope's escape route and then quickly cross with the infantry and move in to destroy him. >

|

| Stuart, plumed hat in hand |

However, it did not work out quite as the Confederates planned. Instead of Stuart launching his raid in secrecy, he himself was raided. Early on the morning of August 18th Stuart was awoken by pickets announcing that cavalry were riding towards his headquarters. Fitz Lee's rebel troopers were expected to arrive from the same direction, but when Stuart rode out to check them out, he realized they were Federals. The Yankee cavalry opened fire, and Stuart wheeled his horse around and galloped off. Jumping a fence he was able to ride to safety, but the Federals were able to capture his headquarters, securing his flamboyant hat and cape, and, more importantly, dispatches from Lee detailing the plan to cut of Pope's retreat. With this information, which corroborated reports from other spys, Pope soon ordered a retreat, and was able to cross the rivers before Lee had a chance to strike.

Thursday, August 9, 2012

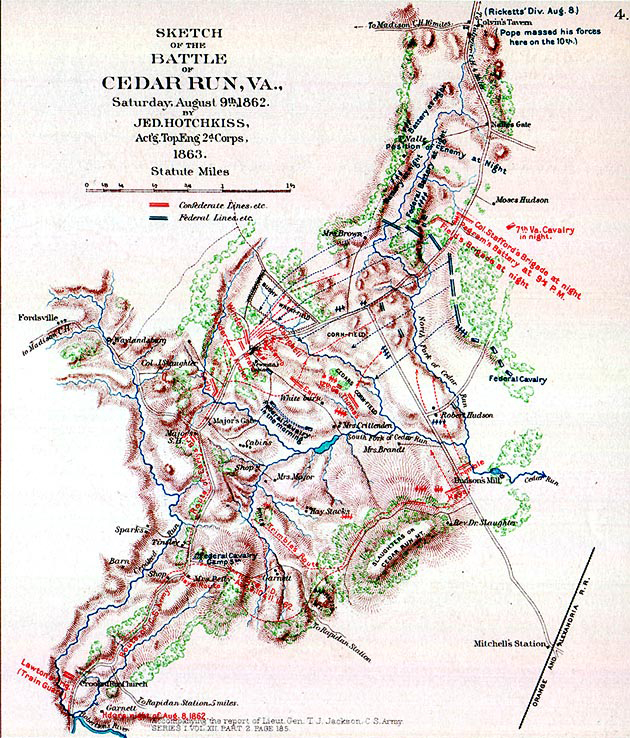

Battle of Cedar Mountain

This post is a few days behind our normal schedule, our apologies for the delay.

Stonewall Jackson began his advance towards John Pope's Army of Virginia in the first days of August. On the 9th he encountered Federal troops around Cedar Mountain, also called Slaughter Mountain. They were under Nathaniel Banks, the old opponent from the Valley Campaign who the rebels called Commissary Banks because of the large amount of supplies they had captured from him. "Get your requisitions ready, boys!" soldiers said as the news went through the army, "Put down everything you want! Old Stonewall's Quartermaster has come with a full supply for issue."

Jackson formed his line along a road running north-south. Ewell on the right was anchored on Cedar Mountain, a commanding artillery position. The left was positioned at a road intersection. The battle opened at 4 pm with an artillery duel. It continued for 1 1/2 hours with 23 Southern cannon in action and a few more for the North. The Confederates, with a converging fire from the mountain, got the better of the engagement. The Federal artillery produced more noise than execution, but one ball found an important mark. Edward Moore, a Confederate artillery soldier, wrote,

Jackson was able to rally the men, and soon the Federal troops were being driven back. Struck by Branch's brigade on the front and the Stonewall Brigade on the flank, they were driven back through the wheat field. By about 7:00 the Confederates were counterattacking, charging Gordon's brigade on the front ad coming on the flank. By dark Jackson had finally won the day. He had come close to being defeated and even personally captured, but his men finally fell into place and drove back the Federals. He was unable to pursue because of the darkness. The North lost 314 killed, 1445 wounded and 594 captured, the Confederates 231 killed and 1,107. At Cedar Mountain Jackson had only defeated Pope's vanguard. The rest of the army remained undefeated, and still outnumbered the Confederate forces. More battles would be necessary for Lee to obtain a complete victory over Pope.

Stonewall Jackson began his advance towards John Pope's Army of Virginia in the first days of August. On the 9th he encountered Federal troops around Cedar Mountain, also called Slaughter Mountain. They were under Nathaniel Banks, the old opponent from the Valley Campaign who the rebels called Commissary Banks because of the large amount of supplies they had captured from him. "Get your requisitions ready, boys!" soldiers said as the news went through the army, "Put down everything you want! Old Stonewall's Quartermaster has come with a full supply for issue."

|

| General Winder |

Jackson formed his line along a road running north-south. Ewell on the right was anchored on Cedar Mountain, a commanding artillery position. The left was positioned at a road intersection. The battle opened at 4 pm with an artillery duel. It continued for 1 1/2 hours with 23 Southern cannon in action and a few more for the North. The Confederates, with a converging fire from the mountain, got the better of the engagement. The Federal artillery produced more noise than execution, but one ball found an important mark. Edward Moore, a Confederate artillery soldier, wrote,

"General Winder, commander of our brigade, dismounted, and, in his shirt-sleeves, had taken his stand a few paces to the left of my gun and with his field-glasses was intently observing the progress of the battle. ... While the enemy's guns were changing their position he gave some directions, which we could not hear for the surrounding noise. I, being nearest, turned and, walking toward him, asked what he had said. As he put his hand to his mouth to repeat the remark, a shell passed through his side and arm, tearing them fearfully. He fell straight back at full length, and lay quivering on the ground. ... He was soon carried off, ... and died a few hours later."Winder was commanding the Stonewall Division, and the command went to William Taliaferro, who because of Jackson's secrecy had no idea of the battle plan. At 5:45 Augur's division advanced against the Confederate center and left. Moving through the high corn, they achieved some surprise although their formations were disorganized. The Confederates kept up a steady fire for about 20 minutes. They were finally reinforced by troops from A. P. Hill whose division was coming up. A soldier remembered the trying advance:

"The field we passed through was an extensive one, and presented to our sight, as we we entered it, almost innumerable bodies of troops fighting, with nothing to protect them save the hand of God. Friend and foe were in open field, and such fighting is seldom witnessed. Troops of all descriptions – horses in every direction, with empty saddles – wounded and dead in all quarters."The Confederate center and right held firm, but the left, held by Garnett's brigade, did not. Reinforcements were slowly moving up, and they were only 10 minutes away. But at 6 pm Garnett's men were overwhelmed by a sudden charged. Coming across the Wheat field the Yankees rushed towards the Gate, the intersection of the two lanes. Garnett's troops stood firm along a fence, firing volley after volley, but the Federals would not stop. Leaping the fence they fought hand to hand, with bayonets and rifle butts, and soon drove Garnett's men into a rout. The Federals continued to push forward and struck a green Confederate brigade in the flank, routing it as well, and sending the entire Confederate center into retreat. Almost the entire Confederate line had been broken by one small Union brigade. But A. P. Hill's men were coming up and several brigades were available to throw into the fight. Jackson himself was at the point of danger trying to rally his men. He tried to draw his sword, the only time he did this during the war, but from disuse it was rusted in the scabbard. So he held up the sword and scabbard in one had and a battle flag in the other. "Rally, brave men, and press forward." Jackson shouted, "Your general will lead you. Jackson will lead you. Follow me!"

|

| The Whitefield looking toward Cedar Mountain |

Jackson was able to rally the men, and soon the Federal troops were being driven back. Struck by Branch's brigade on the front and the Stonewall Brigade on the flank, they were driven back through the wheat field. By about 7:00 the Confederates were counterattacking, charging Gordon's brigade on the front ad coming on the flank. By dark Jackson had finally won the day. He had come close to being defeated and even personally captured, but his men finally fell into place and drove back the Federals. He was unable to pursue because of the darkness. The North lost 314 killed, 1445 wounded and 594 captured, the Confederates 231 killed and 1,107. At Cedar Mountain Jackson had only defeated Pope's vanguard. The rest of the army remained undefeated, and still outnumbered the Confederate forces. More battles would be necessary for Lee to obtain a complete victory over Pope.

Labels:

A. P. Hill,

battle,

Nathaniel Banks,

Stonewall Jackson,

Virginia

Wednesday, August 8, 2012

Bragg Moves North

|

| Bragg |

|

| Kirby Smith |

Before Bragg could move move North, he first had to reach Chattanooga Tennessee. Buell's army was on its way as well, and they had a six week head start. But Bragg had a plan to out wit him. He had been working on repairing the railroad to Mobile, Alabama, and from Mobile to Chattanooga. It was much longer, but it was also much faster. Like Johnston had done at the Battle of Bull Run, Bragg hoped to use the technology of the railroad to make a movement that otherwise would have taken weeks. His men boarded the cars beginning on July 23rd, and withing a week they arrived in Chattanooga, just ahead of the federals. He met with Kirby Smith, who as the Confederate commander in East Tennessee, he would cooperate with in his planned invasion. Together they had 52,000 men, much less that the federal forces. So they intended to follow the example of Jackson in the Shenandoah Valley and destroy the federal armies one by one, moving quickly to avoid being outnumbered.

Labels:

Braxton Bragg,

campaign,

invasion,

Kentucky,

Tennesse

Tuesday, August 7, 2012

Infographic from the Civil War Trust

The Civil War Trust, an organization dedicated to preserving Civil War battlefields, created this really interesting infograph showing Civil War casualty numbers.

Brought to you by The Civil War Trust

Brought to you by The Civil War Trust

Sunday, August 5, 2012

Battle of Baton Rouge

|

| Union troop encampments in Baton Rouge |

|

| Map of the battle |

Breckinridge set out on July 27th, 1862. The Union commander in Baton Rouge, General Thomas Williams soon heard of the expedition. He moved his troops a mile out of town and prepared to meet the attack. His men were inexperienced, as they had trained for only two weeks before being sent out, and it was not known how they would stand in battle. Breckinridge continued to move forward, and arrived just outside the city on the night of August 4th. However, the element of surprise was lost when Union sentries spotted the advance. Nevertheless, Breckinridge determined to continue on with the attack at daybreak.

|

| The Federals charge |

Early in the morning the Confederates set out towards the Union troops. “It was difficult,” said a Confederate Colonel, “to distinguish any object in the thick white mist, or to know friend from foe.” The southern forces encountered the enemy, and with fierce fighting pushed them across the town. Leading a charge at the head of his troops, General Williams was killed, hit in the breast by a bullet. The bitter fighting continued, and the Yankee troops fell back into a prepared position in the town, within range of the river. The Confederates expected to be aided in their attack by the Arkansas’s shells thrown from the river. However, as they attacked the Union troops, it was they who were hit by a navy bombardment. The Arkansas did not make it to the battlefield. Their engines engines failed just four miles above the city. Instead the Federal troops were protected by the guns of their boats in the river. Under this bombardment and meeting fierce resistance from the Federal troops, Breckenridge realized the attack was useless and withdrew. He wrote in his report:

We had listened in vain for the guns of the Arkansas; I saw around me not more than 1,000 exhausted men … The enemy had several batteries commanding the approaches to the arsenals and barracks, and the gunboats had already reopened upon us with a direct fire. Under the circumstances I did not deem it prudent to pursue the victory further.In this fierce fight the Union lost 383 in killed, wounded and missing, the Confederates, 456.

|

| The USS Essex fires into the CSS Arkansas |

The Arkansas, still unable to move, could not escape from the Federla ships, or fight them to advantage. When they sailed up the next day, her commander, Lieutenant Stevens, knew it would be hopeless to resist. Therefore he ordered her to be abandoned and blown up. The Arkansas, which it had seemed could fight with the best the Federals had to offer, had ended in a burning wreck.

The Federals did not long remain in Baton Rouge. Although they had beaten off the attack, they fell back to New Orleans, concerned for its safety. However, they would return that autumn. The Confederate forces occupied Port Hudson a few miles north, which they would hold for many months.

|

| Damage to the town of Baton Rouge |

Labels:

battle,

Earl Van Dorn,

John C. Breckinridge,

Louisiana