There were several movements across the Western

Theater in conjunction with Sherman's advance on Meridian,

Mississippi in February, 1864. One of these was in Dalton, Georgia,

where George Thomas advanced against the lines of Joseph Johnston to

see if his position on Rocky Face Ridge was weakened by sending off

reinforcements to resist Sherman. From February 22-27 the Federals

probed the Confederate positions, but after some heavy skirmishing

they found no weaknesses. The Yankees lost about 300 men, the

Confederates, 150. Johnston had chosen his position well.

Tuesday, February 25, 2014

Thursday, February 20, 2014

Pomeroy Circular

.jpg/300px-Mathew_Brady,_Portrait_of_Secretary_of_the_Treasury_Salmon_P._Chase,_officer_of_the_United_States_government_(1860%E2%80%931865).jpg) |

| Chase |

One issue that loomed large in the mind of

Northern politicians in 1864 was the presidential election that would

be held later that year. It would be the test of whether people

wanted to continue to follow the policies pursued by President

Abraham Lincoln the previous four years. But there were some in the

Republican party that did not even want Lincoln to get a chance at

reelection. 150 years ago today a document called the Pomeroy

Circular was published. It was written by Samuel Pomeroy, a

Republican senator from Kansas. In this document titled, “The Next

Presidential Election,” Pomeroy proposed a new Republican candidate

to replace Lincoln – Salmon P. Chase. Chase was the Secretary of

the Treasury. Chase was aware of the plans of men like Pomeroy and

would have welcomed the opportunity to become President, but he also

did not want to publicly come out against Lincoln unless he was sure

the people would back him. This document was sent to many

Republicans, to help build support for Chase.

|

| Pomeroy |

Unsurprisingly, it was not long before it fell

into Lincoln's hands and was published in the newspapers. Gideon

Welles, Secretary of the Navy, predicted that “it will be more

dangerous in its recoil than its projectile,” meaning that it would

do more damage to Chase than to Lincoln, at whom it was aimed. Chase

wrote to Lincoln that he was not involved in writing the document,

and submitted his resignation, which Lincoln refused. In the long

run, Welles proved to be right. The people did not rally behind the

idea of Chase for president, and even the Republicans of his own

state, Ohio, responded by endorsing Lincoln for president in 1864.

Labels:

Abraham Lincoln,

Gideon Welles,

politics,

Salmon Chase

Battle of Olustee

|

| Olustee |

|

| Map of the battle |

Monday, February 17, 2014

The H. L. Hunley Sinks the Housatonic

|

| The Hunley |

|

| James McClintock, one of the boat's designers |

|

| Plan of the Hunley |

|

| USS Housatonic |

|

| The Hunley underwater |

But many questions still remain. Why did they sink? Did they intentionally dive to wait for the incoming tide and for some reason not surface? Or did the Hunley sink immediately and the wreck gradually move the 1000 feet? Whatever the Hunley's fate, it was unique. Safe and usable submarines were far in the future, and the next successful military use occurred in 1914, during World War I. With the Hunley's sinking, the war was almost over for Charleston. New weapons had been developed and used successfully, but none were powerful enough to break the blockade and turn the war around.

Labels:

battle,

Charleston,

Confederate Navy,

navy,

South Carolina

Saturday, February 15, 2014

Davis Suspends Habeas Corpus

|

| Davis |

|

| Confederate Capitol |

Labels:

Confederate Congress,

Congress,

Jefferson Davis,

politics

Friday, February 14, 2014

Capture of Meridian

|

| Sherman |

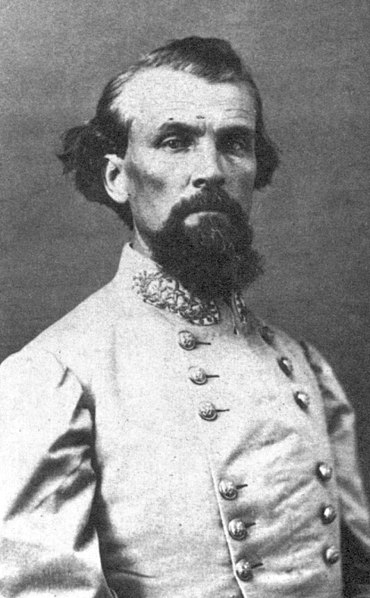

However, Smith would not be coming. The Confederate resistance was led by Nathan Bedford Forrest, and this capable commander forced Smith to turn back. On February 22 he met Forrest in the Battle of Okolona. The Confederate troopers overran the Union barricades and drove them back in a more than ten mile long running battle. The rebel pursuit was eventually halted for lack of ammunition.

|

| Forrest |

Labels:

campaign,

Mississippi,

William Sherman

Sunday, February 9, 2014

Escape from Libby Prison

|

| Libby Prison |

There were many thousands of prisoners captured by both sides in the Civil War. Although many were patrolled or exchanged, many prisons were still needed to hold them. One of the south's famous prisons was Libby Prison in Richmond, Virginia. Before the war Luther Libby owned a warehouse for ship equipment that took up an entire block in the Confederate capitol. When the government needed a prison for Federal officers they used that building, and the old name stuck. The basement was used for storage and cooking, the first floor was the quarters for the guard, and the second and third held the prisoners. However, the kitchen had to be abandoned because of a large number of rats, and the room won the name “Rat Hell.”

Although most of the prisoners avoided “Rat Hell,” three of the Union officers saw it as an opportunity to escape. They found a way to secretly access it by climbing down a chimney in the wall. This alone took fifteen days to accomplish, as they only had pocketknives to remove the bricks. With their plans in place, the prisoners started digging. But before long they hit a snag. They found that the building was built on large timbers. After a tremendous amount of work they were able to saw through those with their pocketknives, but then the tunnel began to fill with water and it had to be abandoned. They tried at another spot to hit a sewer through which they could climb to safety. But when they caused a furnace to collapse they halted that attempt to avoid being detected. It was then decided to go out through the sewer that led out of the kitchen, but days of work were necessary to widen that passage so men could fit through. All was believed to be ready for an escape on the night of January 26th, but the last bit of work took longer than expected, and the tunnel began to fill with water.

|

| Map of the prison and tunnel |

[I]t was impossible to breathe the air of the tunnel for many minutes together; the miner, however, would dig as long as his strength would allow, or till his candle was extinguished by the foul air; he would then make his way out, and another would take his place – a place narrow, dark and damp, and more like a grave than any place can be short of a man's last home.The work would have never been done in normal circumstances, but they were driven on by the hope of escaping from Libby Prison. Another prisoner wrote, “No tongue can tell...how the poor fellow[s] passed among the squealing rats,—enduring the sickening air, the deathly chill, the horrible interminable darkness.”

They work had to stop after several prisoners were able to slip pass the guards. Security was heightened, and the guards began to do roll call. At one rollcall when the prisoners were collected, two were missing, as they were down in the cellar. They were able to talk their way out by saying they had just been missed by the officers doing rollcall. But another time one officer was again in the tunnel during rollcall. The guards decided that he escaped, and the prisoners decided he would have to remain in hiding in the cellar to avoid giving away the plan.

|

| Diagram of the tunnel |

The escape was very successful. 109 prisoners made their way out of the tunnel and walked out of the prison gates without attracting the attention of the sentries. The guards believed that escape was nearly impossible, so they were not particularly careful in keeping watch. When morning came the tunnel was closed and the remaining prisoners tried to hide the large number of missing men. Inevitably the escape was discovered, and pursuit was made. Many of the officers had fought in the area before being captured, so they were familiar with the terrain. 59 of the escapees were able to reach the Union lines, 48 were caught by the Confederates, and two drowned in the James River.

More of this fascinating story can be found in Four Months in Libby, and the Campaign Against Atlanta by Captain L. N. Johnston.