Due to other projects, in the past two weeks this blog has not been updated as often as usual. But since we are right up on the Battle of Gettysburg, here's a post to bring you up to speed on the campaign.

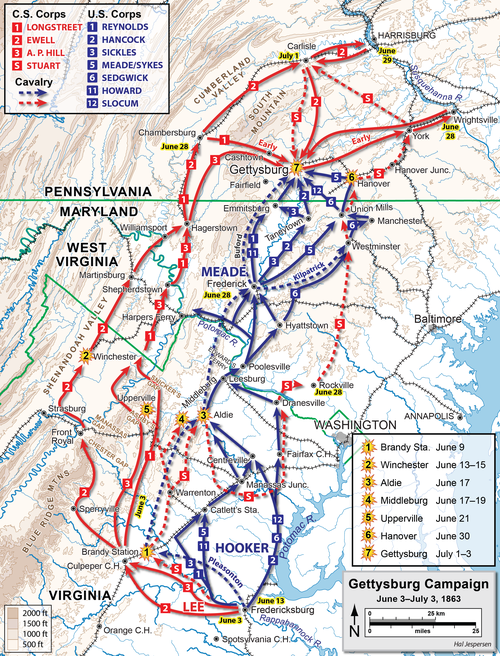

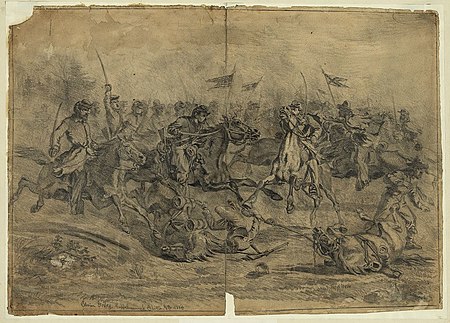

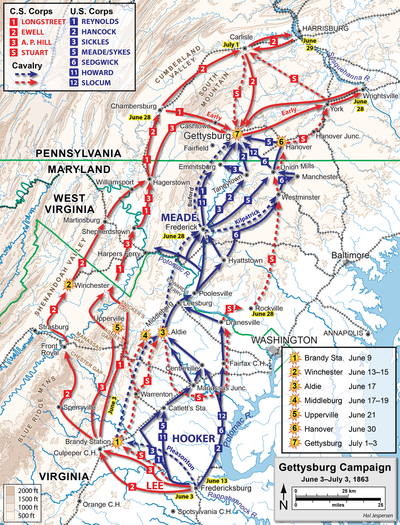

Joseph Hooker, commander of the Union Army of the Potomac, was in a very difficult position. He could get no intelligence of Lee's movements, as his cavalry could not penetrate JEB Stuart's shield guarding the Confederate movements. Hooker wanted a make a strike towards Richmond, since it was being left less protected, but Lincoln however would have none of it. He told Hooker that his objective was to destroy Lee's army and he had to follow him north. Hooker did not begin a serious pursuit until June 25th when he got news that Lee had crossed the Potomac. Meantime, his relations with his superiors was deteriorating. He quarreled with Henry Halleck over whether Harper's Ferry should be defended. When his orders were countermanded, he resigned command of the army. A message for George Meade arrived early on the morning of June 28th ordering him to take command of the army. When Meade was woken by the messengers, he at first thought that he was being arrested. But none the less he took command and tried to acquaint himself with the position of his and Lee's forces as quickly as possible.

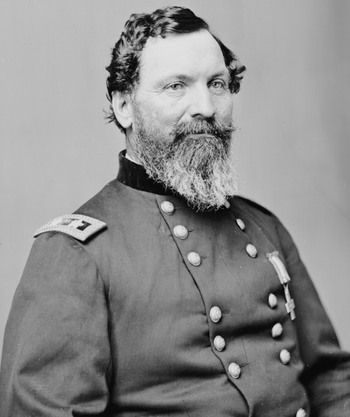

|

| Meade |

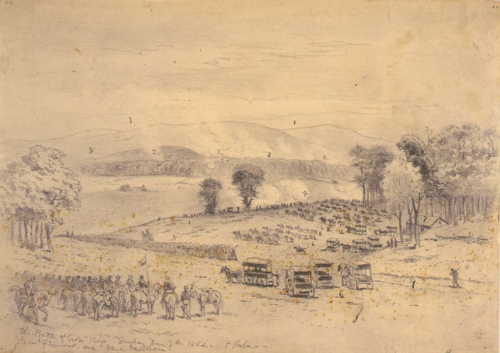

The commanding general has observed with marked satisfaction the conduct of the troops on the march, and confidently anticipates results commensurate with the high spirit they have manifested. No troops could have displayed greater fortitude or better performed the arduous marches of the past ten days. Their conduct in other respects has with few exceptions been in keeping with their character as soldiers, and entitles them to approbation and praise. There have however been instances of forgetfulness on the part of some, that they have in keeping the yet unsullied reputation of the army, and that the duties expected of us by civilization and Christianity are not less obligatory in the country of the enemy than in our own. ...It must be remembered that we make war only upon armed men, and that we cannot take vengeance for the wrongs our people have suffered without lowering ourselves in the eyes of all whose abhorrence has been excited by the atrocities of our enemies, and offending against Him to whom vengeance belongeth, without whose favor and support our efforts must all prove in vain. The commanding general therefore earnestly exhorts the troops to abstain with most scrupulous care from unnecessary or wanton injury to private property, and he enjoins upon all officers to arrest and bring to summary punishment all who shall in any way offend against the orders on this subject.These orders did not mean that the people of the north approved of the treatment they received. A major part of Lee's goals for the invasion was to procure supplies for his army, and they had to come from somewhere. Ewell was sent out ahead with his corps to collect supplies. He would requisition supplies and money from each town along the way. In this he was successful, collecting in two weeks 6,700 barrels of flour, 5,200 cattle, 1,000 hogs and 51,000 pounds of meat.

|

| Stuart |

Lee expected to hear news from Stuart on June 27th or 28th. However, Stuart's couriers were unable to get through to Lee. The absence of Stuart left Lee without his eyes and ears. Although Lee still did have half the army's cavalry, about 2,700 troopers, he did not use them effectively. Lee gave them few orders, and they were not proactive in anticipating his wishes to gather intelligence as Stuart would have been. They did not arrive with the main army until the battle was underway. This lack of cavalry left Lee blindfolded as he moved through foreign territory.

|

| Lee |

We are marching as fast as we can to relieve Harrisburg, but have to keep a sharp lookout that the rebels don't turn around us and get at Washington and Baltimore in our rear. They have a cavalry force in our rear, destroying railroads, etc., with the view of getting me turn back; but I shall not do it. I am going straight at them, and will settle this thing one way or the other. The men are in good spirits; and we have been reinforced so as to have equal numbers with the enemy, and with God's blessing I hope to be successful.Meade had three corps advancing towards Lee under John F. Reynolds, one of his most respected commanders. Behind were two more in a second line, and two out to cover the eastern flank. At the very front of the army were two brigades of cavalry under John Buford to guard the army and gather intelligence. All together Meade had over 112,000 men. He thought Lee had 100,000, but the real number was a bit lower than that. Meade's plan was to fight defensively on ground of his choosing, although he was not opposed to launching an attack if he saw a good opportunity. In accordance with this plan he issued on June 30th what was later called the Pipe Creek Circular, ordering the army to take up a position along Pipe Creek in Maryland. His engineers told him this would be a good defensive position, and it would cover the approaches to Baltimore and Washington. This order was not set out until the morning of July 1st, but before then events were unfolding that would make the Pipe Creek order unnecessary.

Because of his lack of information from cavalry scouts, Lee knew little of the Federals movements until the night of June 28th when a spy working for Longstreet reported. He said he had gone to Washington and knew that the Army of the Potomac had crossed the river and was moving northward. Lee had no choice but to act on this information. The spy was said to be reliable, and he could not ignore a threat to his rear. Therefore he ordered Ewell to abandon his advance on Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, which he was about to capture, and concentrate to the south with Longstreet and Hill to met this new threat from Meade.

As the army was concentrating on June 30th, a brigade of Hill's corps advanced towards the small town of Gettysburg to gather supplies, and there encountered Union cavalry. The Confederates fell back without engaging them. Lee had given orders that none of his commanders were to start a general engagement since the army was not yet concentrated. But A. P. Hill and Henry Heth, the division commander, did not think that there were significant Union forces in Gettysburg. Therefore Hill authorized Heth to continue on a reconnaissance in force to Gettysburg the next day, July 1.