|

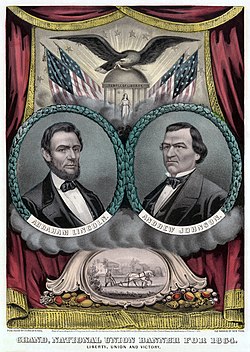

| Sherman |

Instead Sherman would press further south. Sherman believed that war was a terrible thing for both sides. He thought it was his duty to do whatever it took to end it as quickly as possible. No matter the short term suffering it would cause the southerners, it would be justified if it would shorten the war. As he had written to the citizens of Atlanta back in September, “War is cruelty, and you cannot refine it....” His plan was to march from Georgia to the Atlantic Ocean, destroying crops, livestock, and any buildings that would be of use to the Confederacy, and more importantly, breaking the civilians' desire to continue fighting. “I can make the march,” Sherman telegraphed Grant, “and make Georgia howl.”

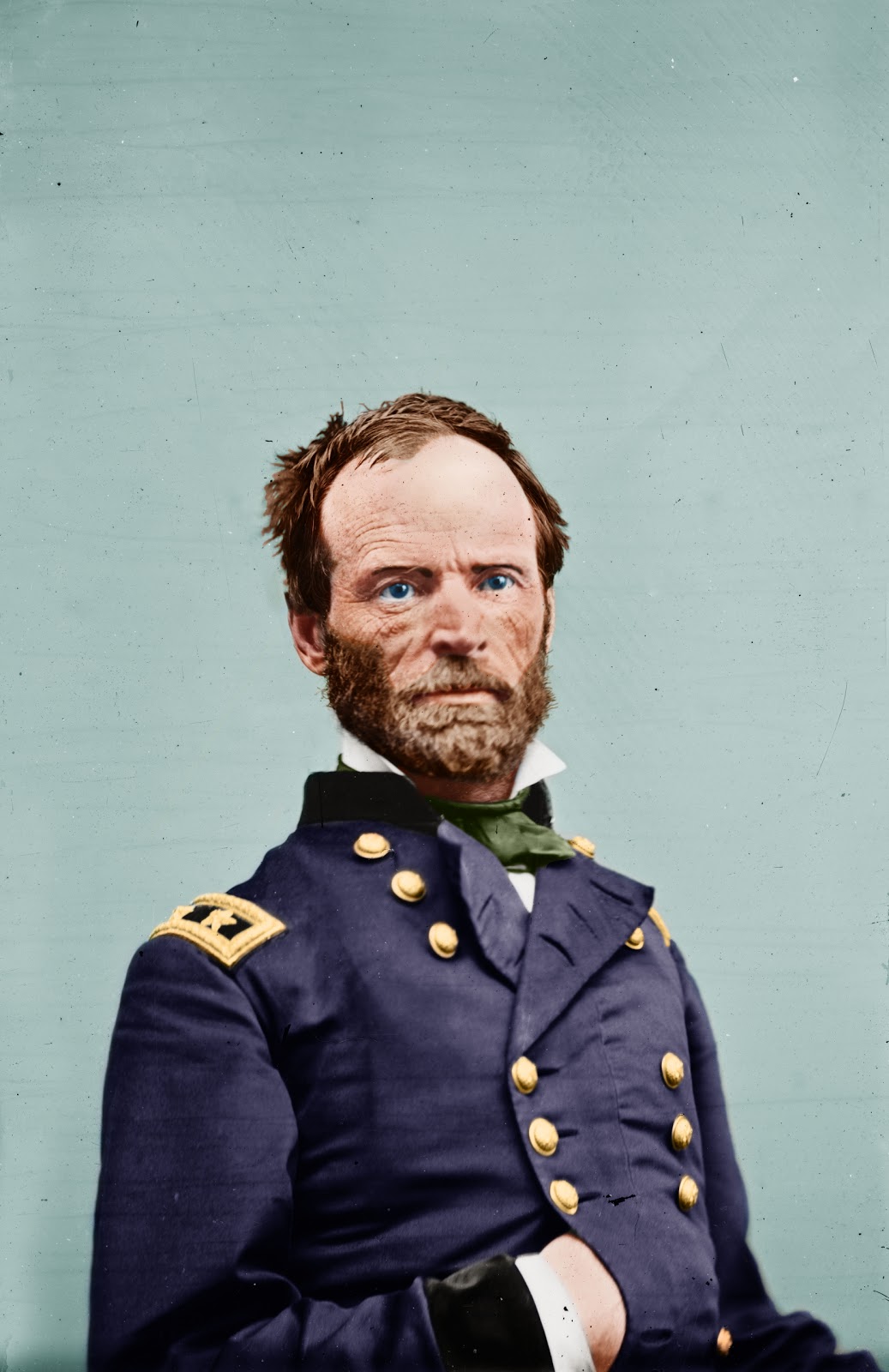

|

| Union Station in Atlanta, destroyed by Federal troops |

The Union army set off from Atlanta on November 15th. Behind them the city burned. It was a fit beginning to the campaign. Sherman's orders were that structures of military use to the Confederates, like the railroad, be destroyed. None the less, the soldiers lit far more than that, and around half the town burned down. As Sherman told one of his staff officers, “Can't save it. … Set as many guards as you please, [the men] will slip it and set fire.” Although his men were officially violating orders, Sherman did not punish the violators. Instead he praised them in his report, writing, “We quietly and deliberately destroyed Atlanta....”

|

| Union soldiers destroying the railroad in Atlanta |

In Sherman's Special Field Orders No. 120, he gave strict rules for the conduct of his men on the march. They were to “forage liberally on the country,” but not to enter homes of civilians. Horses, cattle and other animals could be taken from the population. Buildings were only to be destroyed under orders from the corps commanders, and then only if guerillas operated in the area. The reality was somewhat different. With foraging parties ranging widely, it would have been difficult for the officers to keep the men in check even if they had desired. Sherman's goal for the march was to break the Georgians' will to fight, and if his men sometimes burnt the people's houses, that worked perfectly for his purposes.

By the end of the march the Union army captured 5,000 horses, 4,000 mules and 13,000 cattle, and captured or destroyed 9.5 million pounds of corn and large amounts of other provisions. Sherman estimated that he had done $100 million worth of damage to the Confederate war effort, almost $1.5 billion in today's money. Also destroyed were the railroads, and many mills, houses and barns. Although there was widespread destruction of the civilian's property, it was not complete destruction. Many houses in the wake of his army did escape the torch. As the Yankees marched across Georgia, a crowd of hundreds of escaped slaves followed behind, seeing the Union army as leading them to freedom.

No Civil War era civilian would ever want an army to come through his property. Even when a well behaved army was marching through their home territory, they would often trample crops, burn the split-rail fences for warmth, and maybe butcher some chickens for dinner. Intentional destruction of civilian property was also not unheard of. Jubal Early's Confederate army burnt much of Chambersburg, Pennsylvania on July 30, 1864, when they did not pay the ransom he demanded. But what was different about Sherman was how intentional he was about the destruction. As he told Henry Halleck after the march:

We are not only fighting armies, but a hostile people, and must make old and young, rich and poor, feel the hard hand of war, as well as their organized armies. I know that this recent movement of mine through Georgia has had a wonderful effect in this respect. Thousands who had been deceived by their lying papers into the belief that we were being whipped all the time, realized the truth, and have no appetite for a repetition of the same experience.

Sherman's goal was to make war on civilians, and bring the cost home to their doorsteps. In this he had some success. Many soldiers from Georgia worried about what would happen to their families while they were away, and doubtless the March to the Sea caused some increase in desertion rates from the southern armies. In this way Sherman's march set the stage for the total war of the 20th century. He was one of the American commanders during the war who most clearly recognized the importance of support from the home front for maintaining the war effort, and was willing to take whatever actions necessary to break that resolve.