George Meade

wished to strike Hill as well as Ewell, and he ordered Winfield

Hancock to the area with his II Corps. The corps was spread over many

miles of roads and it took time to bring them into position. Meade

grew tired of the delay, and gave Getty a peremptory order to attack

with what he had. Without Hancock's men the attack did not have the

force to crush the Confederate lines. The forces met in the thick

woods, and each fired through the smoky darkness, unable to see their

enemy. Hancock sent into two of his divisions, but they were unable

to resolve the conflict.

|

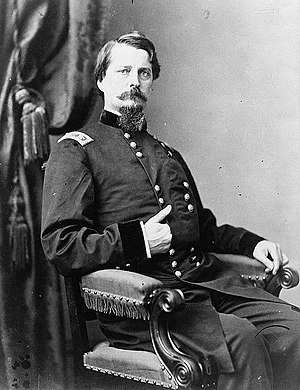

| Hancock |

As soon as the line was formed and dressed, the order to advance was given. Balls fired at Heth's division, in front of us, fell among us at the beginning of our advance. We pressed on, guide left, through the thick undergrowth, until we reached Heth's line, now much thinned and exhausted. We had very imprudently begun to cheer before this. We passed over this line cheering. There was no use of this. We should have charged without uttering a word until within a few yards of the Federal line. As it was, we drew upon ourselves a terrific volley of musketry. The advance was greatly impeded by the matted growth of saplings and bushes, and in the delay a scattering fire commenced along our line.

The rebels gained an initial success, but they soon encountered the same problems that had plagued the Federals. They could not launch a successful charge in the woods of the Wilderness. In an attempt to break the stalemate, James Wadsworth's division of the V Corps was ordered to strike Hill's flank. They headed straight into the gap between the two Confederate corps. The vegetation delayed the advance, but by 7 pm they were nearing Hill's flank. Lee had nothing with which to combat this threat except a 150 man strong battalion from Alabama that had been guarding prisoners. He sent these men forward with a yell, and this small charge was able to convince the Federals to halt their attacks for the night. If the Federals had pressed home their attack, it could have resulted in a disaster for the Southern arms.

Although the

fighting ceased, it was a horrible night for the wounded on both

sides. There had been little rain for some time, and the musketry

ignited the dry woods and fields. The fires quickly spread, and many

of the wounded, unable to escape the flames, had the torture of being

burnt alive. One Federal remembered:

I saw many wounded soldiers in the Wilderness who hung on to their rifles, and whose intention was clearly stamped on their pallid faces. I saw one man, both of whose legs were broken, lying on the ground with his cocked rifle by his side and his ramrod in his hand, and his eyes set on the front. I knew he meant to kill himself in case of fire—knew it is surely as though I could read his thoughts.

0 comments:

Post a Comment