On September 18th Braxton Bragg's advance units encountered the Union army and captured a crossing over Chickamauga Creek. But as had been done several times during this campaign, the Confederates failed to exploit any surprise they might have gained. When he advanced on September 19th, 150 years ago today, the fighting would develop into one of the bloodiest battles in the Civil War.

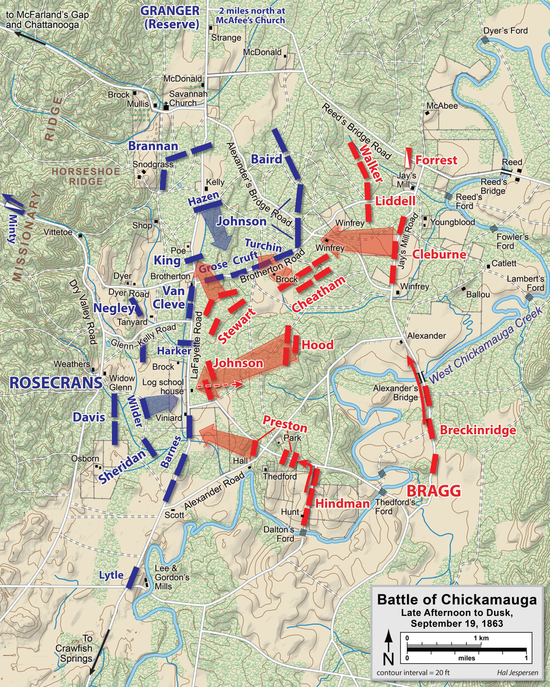

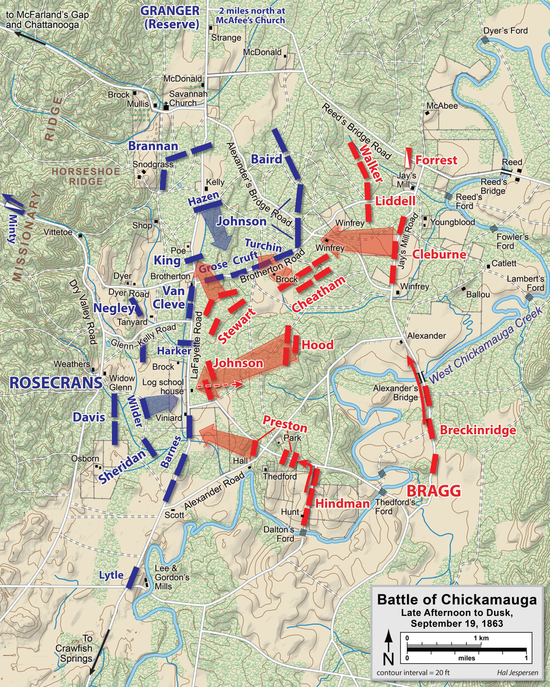

As the Confederate units prepared to move toward the Yankees, they did not know the information on which their plan was based was faulty. The Federal troops were further north than they expected. Bragg had planned to strike Crittenden's crops, at Lee and Gordon's Mill, which he assumed was Rosecrans's left flank. What he did not know was that the Union command had moved Thomas's corps beyond Crittenden. The battle began almost by accident this morning, with a skirmish over water resulting in a Union division being sent to clear off what was believed to be a single Confederate brigade on the west side of Chickamauga Creek. In fact, it was the entire rebel army.

|

| September 19, Morning |

These northern soldiers encountered much more resistance than they anticipated from men which turned out to be Forrest's cavalry men on the Confederate flank. The battle swayed back and forth throughout the morning as each side, threw more men into the increasing fight on the northern portion of the battle. Colonel John T. Wilder wrote this portion of the fight lines which apply well to the entire battle:

All this talk of generalship displayed on either side is sheer nonsense. There was no generalship in it. It was a soldier's fight purely, wherein the only question involved was the question of endurance. The two armies came together like two wild beats, and each fought as long as it could stand up in a knock-down and drag-out encounter. If there had been any high order of generalship displayed, the disasters to both armies might have been less.

|

| September 19, Afternoon |

The fighting was furious in the thick woods of Chickamauga. In the rolling, wooded ground, commanders could see little, and it was what historian Steven Woodworth called “a soldier's battle.”

As the day progressed, each side brought up more troops to add to the battle in the upper part of the field. The third wave of men Bragg threw into the fight was the division of Alexander Stewart. He was ordered to move to the Confederate right, but instead he attacked the left on his own authority. It was an opportune moment, and hitting three of Thomas's brigades around Brotherton Farm, he drove them into a rout after a fierce fight he drove them into a rout. The rebels rushed through the woods after the retreating bluecoats, and succeeded in crossing the Lafayette road. George Thomas brought up two more divisions and threw them into the fight against Stewart, driving the weary men back.

|

| Brotherton Farm |

Seeing an opportunity John Bell Hood ordered in his Texas division from Lee's Army of Northern Virginia to aid Stewart, striking on the left of his position. Hood's gallant boys chard through the woods and again broke the Federal line. Pressing forward, they penetrated so deep that some units were very close to Rosecrans's headquarters. But at this critical juncture two more Federal divisions arrived from the south, and falling into line, halted Hood's men and pushed them back some distance.

|

| September 19, evening |

As darkness was falling over the bloody field, Bragg ordered Patrick Cleburne's men to make another attack on the Union left, where there had been a lull in the fighting. Cleburne's three brigades stretched a mile through the woods, and they rushed forward, striking hard the blue line with twice their numbers. One Federal wrote of the attack:

On they come, in the very face of fire and lead, until the strike the right of our regiment... but when too close to load and fire, the rebels were clubbed over the head and checked for the moment, while, instinctively, both sides recoiled a few steps without breaking the lines, and with that cool, deliberate determination and recklessness which characterizes all soldiers after breathing an atmosphere strongly impregnated with powder smoke, these deadly foes practiced the art of loading and firing in a manner that I believe was never surpassed on any battle field during the rebellion.

|

| Confederate attack |

Cleburne's men pushed the Federals back, but were ultimately unable to break the line. When darkness made further fighting impossible, the men made camp all across the battlefield wherever they happened to be. The Confederates could hear the Federals digging entrenchments that they would have to attack the next morning. Both sides suffered as they lay on the fields over which they had fought. As one Yankee recorded,

How we suffered that night no one knows. Water could not be found; the rebels had possession of the Chickamauga, and we had to do without. Few of us had blankets, and the night was very cold. All looked with anxiety for the coming of dawn; for although we had given the enemy a rough handling, he had certainly used us very hard.

|

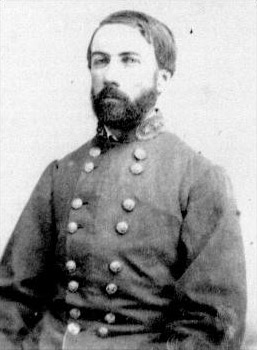

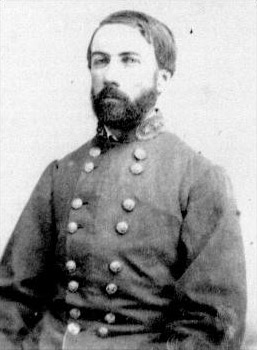

| Daniel Harvey Hill |

The day's fighting was over. The Confederates had hit the Federals hard. On several occasions they had even penetrated the line. But in the end, Union reinforcements arrived and the Confederates were unable to give the final blow to rout them. Confederate General D. H. Hill explained what he thought had hindered their success:

Unfortunately for the Confederates, there was no general advance, as there might have been along the whole line - an advance that must have given a more decisive victory on the 19th than was gained on the 20th. It was desultory fighting from right to left, without concert, and at inopportune times. It was the sparring of the amateur boxer, and not the crushing blows of the trained pugilist.

Bragg did not focus on one area of the Union line and throw all his strength into it. He had come close to victory, two attacks came within sight of the Federal headquarters, but not enough reserved arrived to finish the blow. He moved his focus the line. Aiming everywhere, he hit nowhere hard enough.

Although the attacks had been uncoordinated and the Federals had not been broken, the Confederates were hopeful for the morrow. More of Longstreet's men arrived from Virginia late that night, bringing fresh reinforcements to Bragg. Bragg reorganized the army into two wings, the right was given to Leonidas Polk and the left to Longstreet. This arrangement offended the testy, D. H. Hill, the other Lieutenant General on the field, who was angry that he was not made a wing commander.

On the other side of the field Rosecrans held a council of war with his generals. They agreed that an attempt to attack would be futile, as they had only a few fresh troops and were outnumbered by the Confederates. Rosecrans decided not to retreat, hoping that Bragg would fall back the next day, as he had at Perryville and Murfresborro. But Bragg would not retreat, and the terrible fighting would resume the next day.

0 comments:

Post a Comment