|

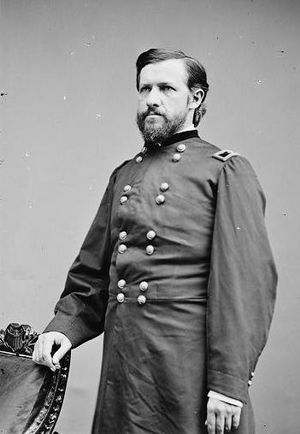

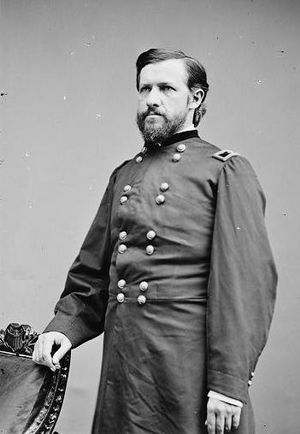

| Ewing |

After the massacre at Lawrence, Kansas on August 21th, it did not take the Federals long to respond. 150 years ago today General Thomas Ewing issued General Order No. 11, which said:

All persons living in Jackson, Cass, and Bates counties, Missouri ... are hereby ordered to remove from their present places of residence within fifteen days from the date hereof.

Those who within that time establish their loyalty to the satisfaction of the commanding officer of the military station near their present place of residence will receive from him a certificate stating the fact of their loyalty, and the names of the witnesses by whom it can be shown. All who receive such certificates will be permitted to remove to any military station in this district, or to any part of the State of Kansas, except the counties of the eastern border of the State. All others shall remove out of the district. Officers commanding companies and detachments serving in the counties named will see that this paragraph is promptly obeyed.

All grain and hay in the field or under shelter, in the district from which inhabitants are required to remove, within reach of military stations after the 9th day of September next, will be taken to such stations and turned over to the proper officers there …. All grain and hay found in such district after the 9th day of September next, not convenient to such stations, will be destroyed.

|

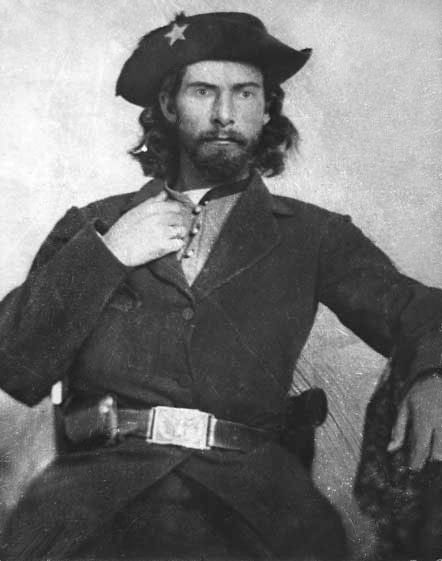

| Bloody Bill Anderson, Confederate bushwacker |

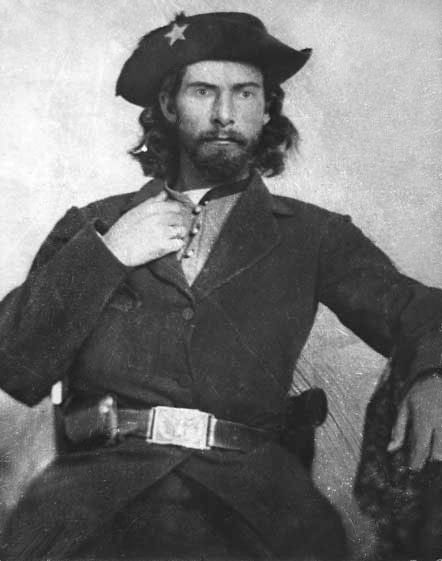

Ewing believed Buskwackers such as Quantrill were able to raid like they did because of the support of the local population. With this order he sought to strike at the root of the problem by forcing the population of Missouri into military stations or out of the area. He was also trying to stop the Union Jayhawkers, lead by Senator James Lane, who wanted to retaliate for Lawrence by destroying a pro-slavery town. But in doing so the Federal troops uprooted families, both southern and northern, destroying their property and leaving the area where they had once lived into “The Burnt District.” The order was also not effective in preventing Confederate guerillas. In fact it made supplies more readily available, as now there was no one to stop them from taking food from the abandoned farms of the settlers. The tragic situation in Kansas and Missouri resulted in great hardships for both sides. A pro-Union artist who was in the area at the time wrote:

It is well-known that men were shot down in the very act of obeying the order, and their wagons and effects seized by their murderers. Large trains of wagons, extending over the prairies for miles in length, and moving Kansasward, were freighted with every description of household furniture and wearing apparel belonging to the exiled inhabitants. Dense columns of smoke arising in every direction marked the conflagrations of dwellings, many of the evidences of which are yet to be seen in the remains of seared and blackened chimneys, standing as melancholy monuments of a ruthless military despotism which spared neither age, sex, character, nor condition. There was neither aid nor protection afforded to the banished inhabitants by the heartless authority which expelled them from their rightful possessions. They crowded by hundreds upon the banks of the Missouri River, and were indebted to the charity of benevolent steamboat conductors for transportation to places of safety where friendly aid could be extended to them without danger to those who ventured to contribute it.

|

| The artist painted this scene of the Burnt District |

0 comments:

Post a Comment