|

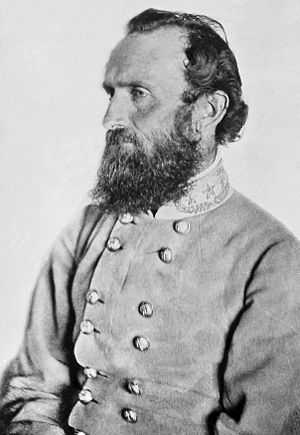

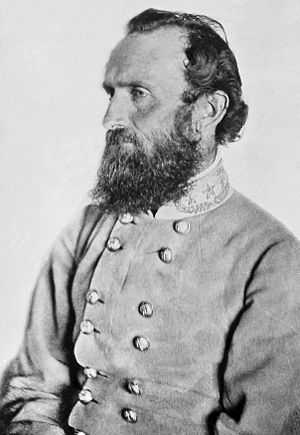

| Jackson |

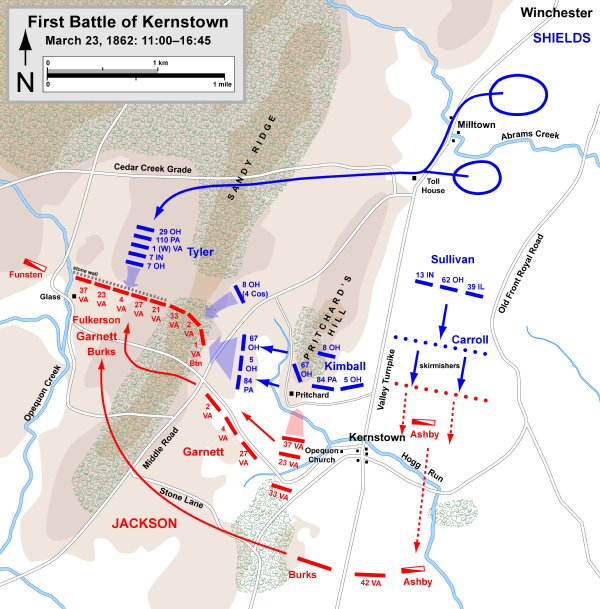

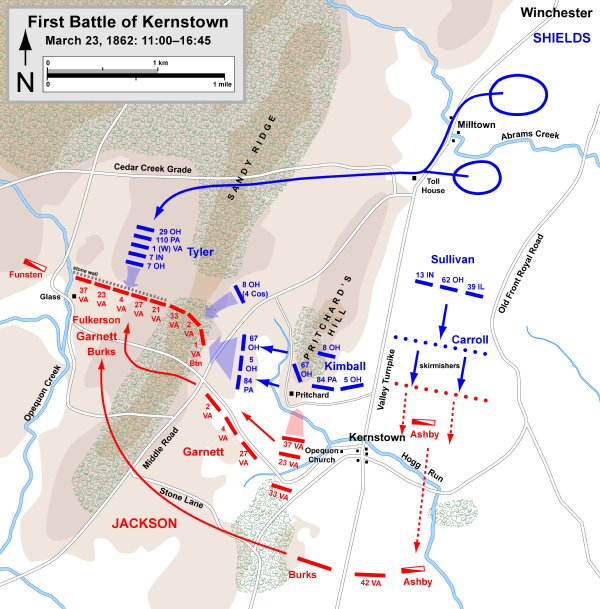

150 years ago today the Battle of Kernstown was fought, marking the beginning of Stonewall Jackson's Shenandoah Valley Campaign, which would be one of the most famous campaigns in the Civil War. General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, who had gained fame at Manassas, had been placed with 4,000 men in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia to guard it against a federal invasion. General Nathaniel Banks was sent to defeat him with 20,000. Jackson was the left flank of the Confederate army under Joseph E. Johnston. When Johnston retreated from Manassas, Jackson was ordered to keep federal troops in the valley without fighting a battle to prevent them from reinforcing McClellan who was attacking Richmond. Jackson kept a watch on Banks and his cavalry commander, Turner Ashby, reported on March 21st that Banks was moving North with virtually all his troops. While Banks was moving, it was only half of his troops he was sending to McClellan. However, Jackson, acting on the incorrect information, decided to attack Banks to prevent him from going to McClellan. By this time Jackson was down to 3,500 men, Banks, 8,500, commanded by Colonel Nathan Kimball.

Ashby opened the battle at 9:00 am. When Kimball moved his troops south, he saw the great strength of Pritchard's Hill, and placed 12 batteries of artillery there. After skirmishing with Ashby for 1 ½ hours, the Confederates fell back and reported to Jackson more forces would be required. Jackson came up with his men, and saw that Pritchard's Hill was key to the position. So putting his men in line, he decided to try to capture the hill by attacking it with two brigades. However, the Federal artillery broke the ranks of the assistants, defeating their attack. Jackson decided to instead try to flank the hill on the Confederate left by capturing Sandy Ridge, which was 100 feet higher. After an artillery bombardment, Jackson sent his men forward. Kimball reinforced the men on Sandy Ridge with a brigade under Colonel Erastus B. Tyler. When Tyler's men reached the ridge, they encountered just one regiment of Confederates behind a stone wall. He ordered his men to charge, without even moving into line of battle. The Confederate volleys broke the formation, and sent the men on their stomachs to escape the Confederate fire. However, the pressure of numbers soon began to toll, but another Confederate regiment came up at just the right time to stabilize the line. The line along the wall continued to be reinforced, and by 4:30 pm it was clear to Kimball that Tyler's brigade would not be able to break the Confederate line. He decided to send in three regiments of troops that had been guarding the artillery on Pritchard's Hill. They hit the Confederate right flank on Sandy Ridge, at right angles to the stone wall. A Federal soldier remembered this:

We were soon at the top-when a scene presented itself that I never will forget. Immediately in front of our whole lines, at a distance of perhaps 80 or 90 yards, was a long wreath of blue smoke settled over a low stone wall – out of this a fire flashed constantly. Between our line and this wall the dead and wounded lay in heaps, while clustered around the starts and stripes, a few heroic blue jackets still fought desperately-some standing, some kneeling, and other lying at full length; but all apparently determined to die right there.

The Union regiments charged and gained a foothold on Sandy Ridge, although they did not break the Confederate line. By this time it was 6:00. The Confederates had suffered heavy casualties and were running out of ammunition. Some soldiers decided to cease fighting and retreat. Jackson met one of these men going to the rear.

One of our company in going to the rear was encountered by General Jackson who inquired where he was going. He answered, that he had shot all his ammunition away, and did not know where to get more. Old Stonewall rose in his stirrups, and gave the command, "Then go back and give them the bayonet," and rode off to the front.

Soon it was not just a few privates that were retreating. Richard Garnett, commander of the Stonewall Brigade on Sandy Ridge, decided of his own accord to retreat without consulting Jackson. He was being attacked on the flank and was out of ammunition. With the Stonewall Brigade gone, the rest of the Confederates on the field soon followed their example. By this time it was getting dark, and a Federal pursuit was unable to catch Jackson while retreating.

|

| Stone wall on Sandy Ridge |

In this battle the Union lost 181 killed, 389 wounded and 4 missing, 8% of their force. The Confederate suffered 139 killed, 312 wounded, 253 captured and 33 missing, 22% of their force. Jackson blamed his defeat on Garnett, and demanded a court-marshal. This trial was never completed because of the battles in quick succession, and Garnett's death in Pickett's charge at Gettysburg. However, it seems likely that Garnett would have been pronounced innocent. Perhaps the real cause for the defeat could be assigned to other factors. Jackson had attacked because of false information, his troops did not have enough ammunition and were tired from long marches. The Confederates were often uncoordinated, and Jackson was sending reinforcements up from the rear instead of leading the battle in the front. Although the Confederates were defeated, it was a strategic victory. The government in Washington feared that Jackson was being reinforced and was planning to attack Washington, so Banks was given 35,000 more men, men which McClellan said he needed for his attack on Richmond.

|

| Pitchard's Hill |

|

| Rise in Sandy Ridge |

For more resources on the Battle of Kernstown or other battles in the Shenandoah Valley Campaign, get our MP3 CD tour on Jackson's Valley Campaign of 1862.

0 comments:

Post a Comment